Mercat cross

By Robert Togneri, Lochmaben – September 2023

What is a Mercat Cross? It is a structure used to mark a market square in market towns, where, historically, the right to hold a regular market or fair was granted by the monarch, a bishop or a baron.

Market crosses were originally from the distinctive tradition in Early Medieval Insular art of free-standing stone or high crosses, often elaborately carved, which goes back to the 7th century. The market cross could represent the official site for a medieval town or village market, granted by a charter, or it could have once been a traditional religious marking at a crossroads.

What does it look like? These structures range from carved stone spires, obelisks or crosses, common to small market towns. In larger market towns, they may be more ornate or covered structures.

The Mercat Cross of Lochmaben now sits in the Princes Street garden, a part of Lochmaben Common Good land2, situated between the Church Hall and Bruce Street (Photo taken 16 October 20083)

It was removed and restored on a modern base. It replaced the ancient cross destroyed in the Albany Raid on 22 July 14844.

Above a moulded cornice there are sun-dials on four sides, and a ball on top as terminal.

Lochmaben is a burgh of very ancient date, although when is difficult to correctly ascertain. Tradition is that it became a royal burgh soon after the accession of Bruce to the throne in 13065.

When the Duke of Albany, the Lord of Annandale, was summoned in 1479 to answer the charges of treason, the summons was executed by the Herald, at the market-cross of Dumfries, and also, “apud crucem fori burgi de Lochmaben” (lit. “at the cross of the marketplace of Lochmaben”) and also at the castle of Lochmaben.

One of the witnesses of the execution at the burgh and castle of Lochmaben, was Robert Henrison, Bailie of Lochmaben6demonstrating in 1479, that Lochmaben was a burgh and had its bailies, and a market cross, at which the process of the law was usually executed.

Like other border towns, it suffered much from the inroads of the English and was frequently burnt and plundered and its charter and records destroyed.

In 1463 Earl of Warwick led an army into Dumfries-shire, burning the town of Lochmaben and in 1484, the Earl of Douglas and the traitor Duke of Albany attempted to plunder Lochmaben on St Magdalene’s fair day7 (22 July); but they were disappointed8.

The charter of “novo damusi” (lit. “I have given a new”) granted the 16th July 1612, by James VI. He gives as a reason for its renewal, that the burgh records had been destroyed when it was burnt by the English. This charter confirms all former charters which had been burnt, and it grants of new to the said burgh all the lands belonging to the same. It also gave full power to the inhabitants to elect magistrates for the government of the people thereof. William Maxwell sat in the Scots Parliament, as commissioner for the burgh of Lochmaben in October 1612. This is the first instance that can be traced of its representation in Parliament9.

Burgh Boundaries & Privileges

In 1845 Lohmaben Burgh contained about 1,000 inhabitants, 39 of whom have votes under the Reform Bill (1832) for a member of Parliament. Lochmaben Burgh was one of the few which did not come under the spirit of the Reform Act, which would have led to a loss of power (which perhaps was its greatest) as one of the five Scottish burghs which returned a member to Parliament.

Arising from the charter which narrates that His Majesty’s “most noble ancestors, of most worthy memory, and beyond the memory of man, had erected the town into a free burgh royal, and had given to the burgesses and inhabitants divers and various lands, fishings, profitable farms, and possessions of the same”.

The bounds of the Burgh were proscribed in the charter, a territory embracing nearly two thousand acres, stretching from Marjorie syke, now Marjorie banks, and the burn from Halleaths Loch, on the northeast, to the barony of Torthorwald on the southwest, and from the Marlake and Harthat style, including Thorniequhat, on the southeast, to Belzies, Elshieshields, on the northwest.

The King, “considering the very many faithful and acceptable services done to us and our predecessors by the burgesses and free inhabitants of the said burgh of Lochmaben in all time past”, confirms the ancient erection, and of new grants and dispones all and sundry the lands, fishings, forests“10).

Certain powers and privileges were conferred, for the erection of manufactories of woollen, linen, and all other kinds of commerce, “called the staple guids;” and to admit various trades and crafts, to build a court-house and market-cross. The people of the Burgh were given the right to hold market “every week, on the Sabbath day; to have two free fairs in the year, viz., upon the days of St Magdalen and Michaelmas, and of holding the same for eight days.”

Jurisdiction in both criminal and civil matters is conferred—” heading, hanging, drowning, and sending into banishment, all transgressors and delinquents.” Amongst other privileges, is that of “pit and gallows,”.

In fine, the king wills that the provost and bailies shall exercise and use “all and singular all privileges, immunities, and liberties whatsoever, as freely in every respect as any other royal burgh within this our kingdom can use or exercise.”

This is the substance of King James’s charter. Four hundred and thirty-one years have passed since it was granted(as of 2023!); and, alas! with them, too, the wealth of one of the best-endowed burghs in Scotland!11

Lochmaben’s Cross A market cross, as described above and formerly situated outside the southeast corner of the Toll Booth – now Lochmaben Town Hall, was removed before 1958 to its present position on common ground in Princes Street, Lochmaben adjoining the church hall and overlooked by the Crown Hotel in Bruce Street. The Market Cross is a pillar, built on a modern base, surmounted by a moulded cornice and above a cross with sundials on four sides, and a ball on top as a terminal. It is a relic chiefly remarkable for its original costliness!

When the cross, which was standing in l479, was destroyed, there is a story telling how the magistrates got the present one erected for the time being. At the time the castle of Elshieshields was built, some of the building materials were unused, and Lochmaben being without a cross, which was indispensable in all burghs, the town council in exchange for these materials to erect the cross, made over to the laird of Elsieshields (the Johnstones), his heirs and successors, the “mill and mill lands of Lochmaben, being a part of the burgh property, from which lands the present proprietor draws £100 Sterling“12) and 13

This is an example of burgh mismanagement14 which gave the Johnstones complete control of Lochmabens Flax and Corn Mills which were productive. In the 19th century large quantities of flax were raised in this parish, which was manufactured into cloth and sold unbleached in England to the amount of 60,000 yards annually15.

The Markets

The town, as described in 1845;

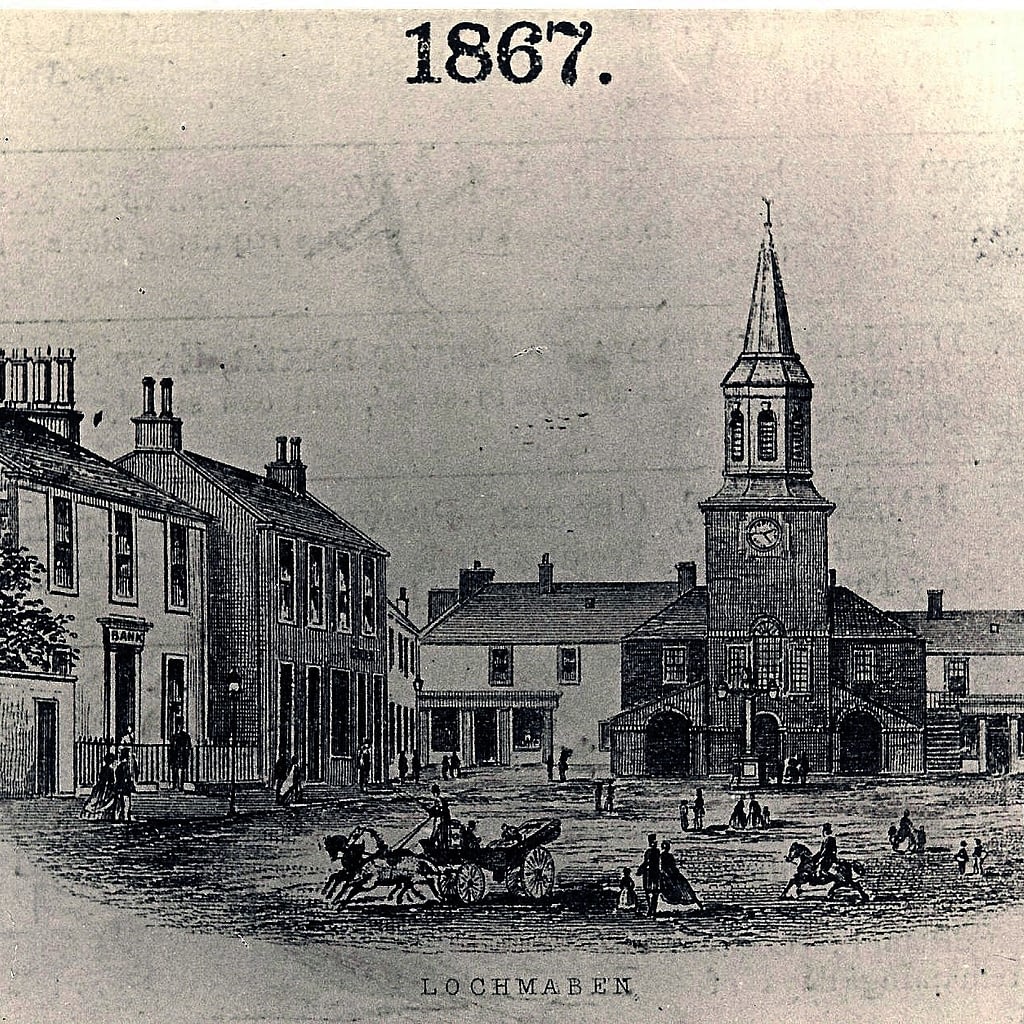

“...is built in a regular manner. Its High Street is wide and spacious. At the south end of this street stands the parish church, and at the north end of it the Town Hall and market-place. The street here is very broad, and admirably adapted for the fortnightly pork markets, and the weekly canes for butter, eggs, dairy farm and other produce, recently established in the town. By the activity of the present magistrates and a few other respectable inhabitants, markets have again been regularly instituted. There are two principal fairs in the year for hiring farm servants, which are numerously attended, the neighbouring farmers giving them their support. The burgh is governed by a provost, three bailies, a dean of guild, a treasurer, and nine ordinary councillors. There are five incorporated trades, which annually elect their deacons and office bearers; and the deacons with the masters of craft, choose their convener; but none of them ex officio are members of the town council. The revenues of this burgh are very small, arising from the feu duties and customs which are collected within the burgh roods. These funds are at present under the judicial management of the Lords of Session1. The Town Hall surmounted by a spire with a clock facing the South is small and not altogether inelegant, especially as seen when entering High Street from the East, the upper apartments therein are set apart for Town Council Conventions, but when opportunity offers, they are readily let out to itinerant dancing masters. Down on the ground floor there is a loathsome Lock-up or Jail also an apartment in which the Meal Market is held. Under which there is the jail and a lock up house, with an arched space in front for weighing the different commodities brought to market.”

- “Mercat n.”. Dictionary of the Scots Language. 2004. Scottish Language Dictionaries Ltd. Accessed 13 Sep 2023 http://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/mercat[↩]

- Common Good Register https://www.dumgal.gov.uk/article/15778/[↩]

- Lochmaben Mercat Cross and Manse cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Chris Newman – geograph.org.uk/p/1009576[↩]

- A Short History of Scotland by Andrew Lang (1911) Chapter XIII. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/15955/pg15955-images.html[↩]

- https://www.royal.uk/robert-i-r-1306-1329 [↩]

- The New Statistical Account Of Scotland (1845). Vol. Iv. Page 391 – https://www.electricscotland.com/etexts/NewStatisticalAccountofScotland04.txt[↩]

- St Magdalene – https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=83[↩]

- The New Statistical Account Of Scotland (1845). Vol. IV. Page 392 – https://www.electricscotland.com/etexts/NewStatisticalAccountofScotland04.txt[↩]

- The New Statistical Account Of Scotland (1845). Vol. IV. – https://www.electricscotland.com/etexts/NewStatisticalAccountofScotland04.txt[↩]

- Annandale was at one time densely covered with trees. The burgh lands afford abundant evidence of this, not only by the large trunks found in the mosses, but by the names of places, as Aik-rig, etc. (See proceedings against James Mounsey in 1504, for destroying the woods of Lochmaben, &c., Appendix K.[↩]

- ((The New Statistical Account Of Scotland (1845). Vol. IV. Page 392 – https://www.electricscotland.com/etexts/NewStatisticalAccountofScotland04.txt[↩]

- £100 in 1845 is worth £15,556.47 today (September 2023[↩]

- This Property (in 1846) now yields an annual rent of £100 (worth £15,556.47 today – September 2023) which may in some measure account for the Bankruptcy of the Parish. Ordnance Survey Name Books, 1848-1858 Dumfriesshire volume 36 https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/digital-volumes/ordnance-survey-name-books/dumfriesshire-os-name-books-1848-1858/dumfriesshire-volume-36/2[↩]

- See also 1776 sale of commonty land https://lochmaben.org.uk/go-native/heritage/the-mills/kinnel-mill/[↩]

- Parish Of Lochmaben Presbytery Of Lochmaden, Synoid Of Dumfries The Rev. Thomas Marjoribanks, Minister I.–Topography And Natural History: Lochmaben, County Of Dumfries, ((The New Statistical Account Of Scotland (1845). Vol. IV. Pages 391 to 394 – https://www.electricscotland.com/etexts/NewStatisticalAccountofScotland04.txt[↩]