Auctoritas Romana Lochmaben (The Romans in Lochmaben)

Prepared by Robert Togneri, Lochmaben: August 2023

Roman arrival in England

Julius Caesar1 2, a frequent visitor to conquered Gaul, heard tell of a wild country in the North Sea that lay two hours’ sail from the coast of France.

Few visited save the adventurous merchants of Gaul, and traders from the Levant, who exchanged the products of the East for the tin of the Cornish mines. The white cliffs of Dover can be seen from France, a land Rome was not mistress of, raised the thirst for conquest and occupation3.

A year later Caesar embarked his forces and left never more to return. “The deified Julius,” says Tacitus4, “though he scared the natives by a successful engagement, and took possession of the shore, can be considered merely to have discovered, but not appropriated, the island for posterity5.”

After this, Britain had rest from the Roman invasion for the space of ninety-eight years. But if the legionary was unseen in the land, the Italian merchant found his way and settled in its cities, Caesar having shown the country to them. The reigns of Augustus6, Tiberius7, and of Caligula8 followed and passed peacefully.

In the time of the emperor Claudius9, an effort was to subjugate the country. In AD 43 Aulus Plutius10 came to Britain at the head of an army of 50,000 men. He entered the country unopposed and fought numerous battles. He carried the Roman arms from the Straits of Dover to the Tweed.

Roman arrival in Scotland

Before the year AD80, not a legionary had crossed the Tweed. Another half-century was to pass before the march of the Roman arms should reach Caledonia11. Scotland was among the last countries, in part, destined to submit to an empire, now paralysed by political and moral corruption, itself about to fall.

About 78AD the general who carried the Roman sword into Scotland, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, was appointed governor of Britannia. He was one of the ablest that Rome had sent forth on the conquest of Britain. He combined the qualities of the statesman with those of the soldier and retained by wisdom what he won by valour.

His predecessor Cerialis12, was primarily concerned with pacifying and Romanizing the local tribes, but Agricola had more “glorious” intentions. He wasted no time in carrying out a devastating campaign against the Ordovices13 in Wales and various other northern British tribes.

Tacitus paints him as a model of military virtue, trained to the knowledge of affairs by service in various grades and in many fields and used his power and position wisely and fairly. This portrait, drawn by the pen of his son-in-law, may be gilded on the part of the historian. But after all deductions, Agricola stood far above the average Roman of his day.

If he dealt the enemy a heavy blow, he followed it up with offers of peace: he was at once severe and conciliatory. This was the man who now came to subjugate Scotland to Roman obedience14.

The southern province of England was not secure so long as the more warlike north remained unconquered: the tempest would ever be gathering on the great mountains and rushing down with destructive fury on the lowlands.

Every successive Roman governor who entered Britain had it as his special task and highest ambition, to conquer Caledonia and affix to his name the much-coveted designation of Britannicus15.

Agricola was at the head of a powerful and well-disciplined force, well-versed in the command of armies. Before setting his sight on Caledon, he took precautions to appease the southern Britons by;

- equalising and lightening the heavy taxes which his predecessors had imposed upon them.

- striving to draw them from arms and into channels of industry.

- embellishing their country with temples and towns.

- educating the sons of chieftains in the accomplishments and arts of Italy.

- educating the youth to use the Roman tongue, and to wear the Roman toga.

- In these soft indulgences, they forgot the ardour of resistance to the invaders.

There is a strong undertone of contempt in the words of Tacitus when he describes these changes. “Baths, piazzas, and sumptuous feasts,” he says, “Were called by the ignorant people ‘civilisation.’ They were in reality the elements of slavery.16”

Lochmaben is joined to the Roman Empire

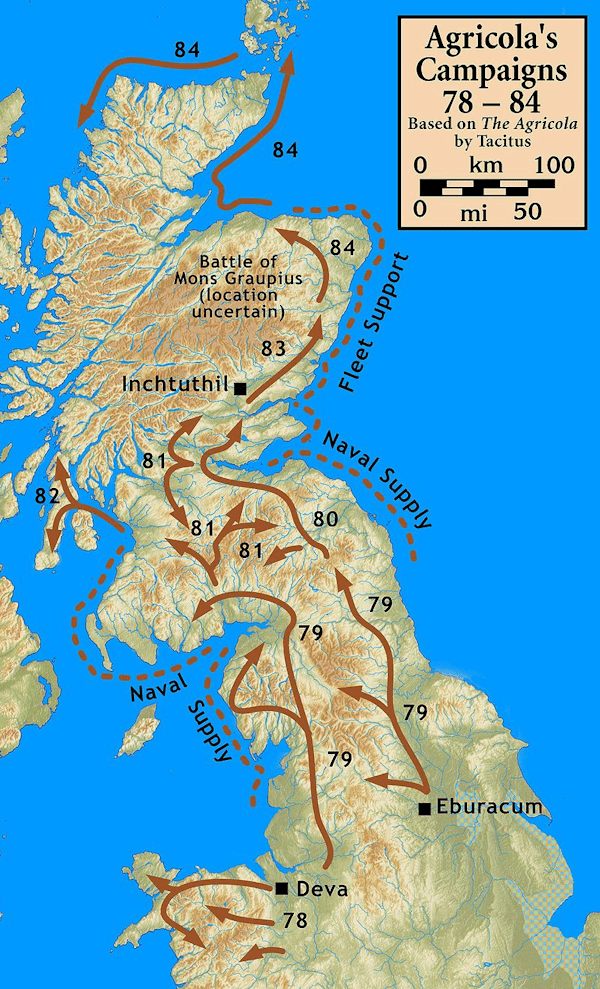

In 79 AD, Emperor Vespasian17 died and Agricola was ordered by his successor, Titus18, to conquer the whole of the island of Britain, and in early summer, invaded Caledon – the outline map highlights Agricola’s advances19.

Even after he had crossed the Tweed and the Esk, he did not, all at once, come in contact with the true Caledonian fierceness.

The countryside, a formidable ally of the natives, provided significant challenges, particularly in the east with the Cheviots, the Southern Uplands and Galloway. The hills, the rocky glens, the woods, and the morasses allowed the Caledonian to lurk and spring upon the Romans, entangled in bog or caught in a defile.

Agricola saw the hit-and-run tactics would test the endurance and bravery of his troops, all the while exercising his wariness and skill. He dared not turn back before barbarians, as other Roman Generals found failure to achieve victory in military campaigns could result in a loss of trust and sometimes even punishment or exile by the Roman authorities.

So to the unknown north, where the Roman eagle had never yet been seen, Agricola advanced deep into the forests of Caledon.

Those who submitted experienced clemency: those who opposed paid a price. The carnage the conqueror left behind him, and the terrible rumour that travelled in front of him, opened his way into the land, and without fighting a single battle he reached the summit of the Lammermoors, whence he looked down on the plains of the Lothians and the waters of the Firth of Forth.

Having already pacified the Votadini tribe20 in the eastern lowlands, his sweep across the central lowlands was bloody and decisive. Under assault by two legions, the Selgovae tribe21 in the west was decimated.

On reaching the Forth and Clyde valleys, he secured his position with a turf wall between the rivers (This wall would be the foundation for the Antonine wall 60 years later22). In the remainder of the year, he consolidated his position ensuring a non aggression pact with the western tribes of the Damonii23 and the Novantae24.

Lochmaben was now part of the Roman Empire, possibly under the name Locus Mapon25.

Sadly there is little direct information of the Romans in the Lochmaben and Lockerbie areas, there is an awareness of Roman influence and occupation in the local area but little has been explored in any depth. One of the most interesting resources is the “Roy Map of Scotland26”.

Following the Jacobite Rebellionix (1745-1746) English military commanders in Scotland found themselves ‘greatly embarrassed for want of a proper Survey of the Country‘27.

Colonel David Watson, then Deputy Quartermaster-General promoted the idea to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland. Soon after his victory at Culloden, Cumberland successfully petitioned King George II (his father) for the Military Survey of Scotland and in 1747 Watson was instructed to begin work. He delegated the primary practical responsibility to his Assistant Quartermaster, William Roy.

William Roy (1726-1790) was born at Miltonhead, near Carluke, the son of an estate factor and attended the grammar school at Lanark. From 1748, assisted by six surveying parties; the Highlands were largely complete by 1752, while southern Scotland (south of the Forth-Clyde line) was completed by 1755. He reached the rank of Major-General by 1781 and promoted the idea of a complete triangulation of Britain incorporating his Military Survey of Scotland as a basis for better mapping. Through his efforts the accurate measurement of a baseline on Hounslow Heath laid the foundation of the Trigonometrical Survey of Great Britain in 1791. This was later to become the Ordnance Survey28.

Examining the Roy Military Map of Scotland, specifically Roy Lowlands29 allows us to see the influence of the Romans in Scotland at a time just before major changes to the landscape and development of modern Britain was to occur at pace.

From the western end of Cumberland Agricola’s forces advancing from Carlisle crossed the mouth of the River Esk at Mossband and established a road from there north passing Old Graitney (Gretna), Cove (Kirkpatrick Fleming), Wiseby (Kirtlebridge) until midway between Eaglesfield and Middlebie at the confluence of Mein Water and Middlebie Burn the fort of Blatobulgium (Birrens) Vicus30 was built, although excavations suggest it was built as an outpost of Hadrian’s wall (begun AD 122) it likely that Agricola’s forces established an earlier base there.

From Blatobulgium the road continues passing Birrenswark (Burnswark) on the west side. Heading north two routes diverge

- the eastern route goes direct to Whitewoollenhass (Quytewoolen) where it is believed there was a signal post easily seen from another signal post on the summit of Burnswark which in turn is easily seen from Cumberland. This route continues north to the Water of Dryfe crossing the ford (now Dryfebridge) and continues north towards Moffat and Edinburgh principally along what is now the A701.

- the western route goes to Lockerby (Lockerbie) where it crosses the ford on the Water of Dryfe (near the site of the Battle of Dryfe Sands (1593). This also connects with the site of Roman Encampment at Torwood Muir.

This route continues to the ford on the River Annan near Broadholm and over to Broomhill and on through what is now Marjorie Banks. The road stops at the site of Woody Castle which Roy wrongly assumed was a wooden Roman Encampment he names Wood Castle on his maps, although given its prominent and defensible location it may indeed have been used as such. Current belief is that it is much older, dating to the Iron Age31. From here the road continues around Pinnacle Hill and down to Amisfield before continuing both north and west.

A route map

The map shows the progression from Carlisle north to Lockerbie and Lochmaben and is one of many routes in and through Scotland.

Map key – Notable points are marked by numbers in circles e.g. ①, routes are marked by coloured lines and some sites are outlined areas which may only be visible when you zoom in on the interactive map.

① Advancing from Luguvaliu32 (Carlisle) – The Roman army forded the River Esk from the edge of the Rockcliffe Marsh to Mossband Marsh and then crossed the Sark at Old Graitney (now Gretna) where they established soldiers camps at Annan and Gretna Green.

Focusing on the Gretna route a road was established heading north paralleling what is now the A74(M) until Eaglesfield. At this point, the road turns to Middlebie.

Midway between is the site of the Roman fort of Blatobulgium, a study of the site reveals important insights into the Roman presence in the region. Findings suggest the fort was established in the 1st century AD and played a significant role in controlling the northern frontier of Roman Britain. Excavations have uncovered evidence of military structures and daily life, including barracks, fortifications, and artefacts.

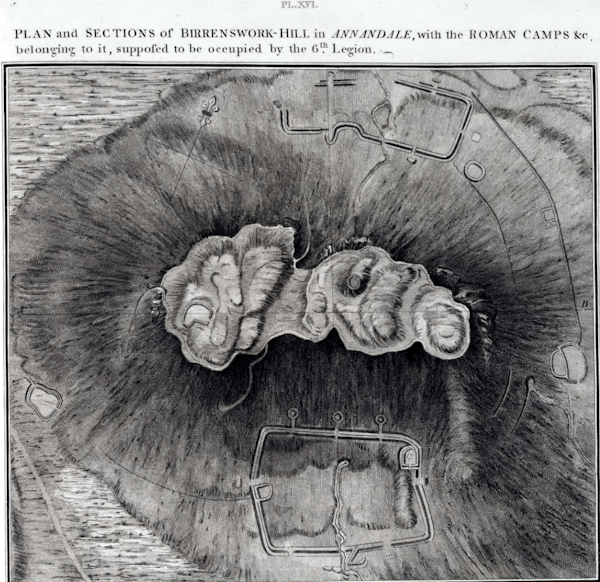

A short distance north of Blatobulgium lies the flat-topped hill of Birrenswark (Burnswark). A dominant location clearly visible from Cumberland and likely saw fierce fighting between the Romans and the local tribes.

② Burnswark Training Camp 1 is the southerly of the two training camps around Burnswark Hillfort. The earthwork is closer in form to the more usual rectangle. It measures about 260m from north-east to south-west by around 194m, enclosing almost 12 acres. There is a spring bisecting the camp, known locally as ‘Agricola’s Well’.

Exploration around Burnswark includes the discovery of lead sling bullets and other artefacts related to siege warfare. These findings suggest that Burnswark provided a training ground for Roman soldiers, particularly for honing their siege warfare skills, two camps are known to have existed, one on either side of the hill.

③ Roman signal posts on high ground were used as a communication system. Known as “centumviral towers” they were strategically placed to relay messages using a system of torches or smoke signals.

They played a crucial role in military and administrative communication, allowing rapid transmission of information across long distances. These signal posts were instrumental in maintaining Roman control and facilitating efficient communication within the empire.

The location on prominent hill tops of Birrenswark (Burnswark), Whitewoolenhaas (Quhytewoolen Hill at Lockerbie), Pinnacle Hill (Lochmaben / Shieldhill) would allow clear lines of communication.

④ Torwood Camp discovered by Roy in 1769 on heathland north-west of Fairholm, parts of this camp have been incorporated into field boundaries. The Roman defences are best observed at the north west where the rampart survives as a mound 14 feet across.The two titulus outworks noted by Roy on the west now lie in a plantation; they were clearly visible in the 1950’s. The north side of the camp was clearly visible for the first time, from the air, as crop marks during the early 1960s.

⑤ The Battle of Torwood Muir took place about AD 83 between General Gnaeus Julius Agricola of the Roman Empire and Corbredus Galdus35, the King of the Caledonian Scots. Agricola’s Roman forces emerged victorious, leading to increased Roman control in Scotland.

This battle marked a significant Roman advancement into northern Britain and contributed to Agricola’s reputation as a successful military leader.

⑥ Ladyward Fort36 was a type of Roman military fortification located on the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire. These forts were typically smaller than traditional military forts and served as outposts or watchtowers.

Trenching has established the whole of the north side, 518m long, and the north west angle of this camp, discovered from the air in 1967. Cropmarks confirmed by trenches at two points show that the east side was not less that 472m. The camp encloses the whole of a small hill between Castle Loch to the south and the former Halleaths Loch, drained in 1846, to the north.

A camp of 25.5 hectares would lie symmetrically on the hill and closely match in size and proportions the camp of 25.2 hectares at Dalswinton, 17km to the west. Nothing is visible on the ground.

⑧ Wood Castle or Woody Castle38 is situated on a low eminence in cultivated ground and represents the type of Dumfriesshire circular fort which often goes by the name of Birren.

It is the remains of a fort believed to be Iron Age. It stands on a natural hillock overlooking Upper Loch and Mill Loch.

Both lochs were once larger, when built, the fort would have been partly surrounded by water and marsh.

The remains contain the inner portion of defences, the outer elements having been ploughed almost flat over the past century. It is 60m across internally, edged by a massive rampart with a wide, deep outer ditch. The entrance has been on the east-north-east. The outer enclosure is now only on aerial photographs.

The Reverend Robert Wallace, Minister of St Michaels describes the route of the Roman Road passing here and says it “touched an entire and beautiful double fort39”.

Part of the Roman Road, constructed of paving slabs and passing Woody Castle is said to remain buried under the field.

⑨ Murder Loch Roman Fortlet((https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/places/murder_loch/)) measuring roughly 60 metres square with a single entrance gap on the south-east.

This is about 50% larger than the Flavian series of fortlets based around Drumlanrig along Nithsdale to the north-west and is thought to be an Antonine foundation, guarding the western supply route for the Antonine Wall.

⑩ Amisfield Marching Camp((https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/places/amisfield/)) is a large camp that was discovered from the air in 1984. Almost its entire perimeter is recorded. It was aligned north-south, not on the suspected Roman road through the area which ran east-west.The camp at Amisfield Tower encloses the summit of a low hill close to the presumed line of the Roman road from Annandale to Nithsdale. It measures 385m by 316m enclosing around 30.1 acres.

Without a doubt, Lochmaben held significance for the Romans, as a substantial portion of their military forces travelling north and west would pass through this region. The Romans ultimately withdrew from Scotland in AD 410, after three centuries, without ever completely subduing and ‘civilizing’ the area.

It is probable that Lochmaben maintained its importance into the early medieval era, contributing to the Kingdom of Northumbria before ultimately becoming integrated into the Kingdom of Scotland.

- Picture of Ceasar by Ruebens https://www.theleidencollection.com/artwork/julius-caesar/[↩]

- Note: the letter ‘U’ does not exist in Latin – the letter ‘V’ appears in its place – for ease of reading the ‘U’ has been left in![↩]

- History Of The Scottish Nation: Vol 1, Chapter 16 – Roman period of Britain; England invaded by Caesar, and Scotland by Agricola https://www.electricscotland.com/history/wylie/vol1ch16.htm[↩]

- While invaluable as an ancient source, his work is tainted by the fact that he was the son-in-law of the general Agricola. Much of his work may have been embellished to lend support and glory to Agricola and Rome, as was common with ancient sources[↩]

- Tacitus, Vita Agricoloe, c. 13. https://la.wikisource.org/wiki/De_vita_et_moribus_Iulii_Agricolae and https://oro.open.ac.uk/64702/1/27919387.pdf[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustus[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiberius[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caligula[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claudius[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aulus_Plautius[↩]

- https://www.unrv.com/provinces/caledonia.php[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quintus_Petillius_Cerialis[↩]

- https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsBritain/BritainOrdovices.htm[↩]

- Tacitus, Vit. Agric., c. 4, 5, 8. https://www.electricscotland.com/history/wylie/vol1ch16.htm[↩]

- Britannicus was given to Claudius in AD 43 after his conquest of Britain. Claudius never used it himself and gave the name to his son instead, and his full name became Tiberius Claudius Caesar Britannicus. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Britannicus[↩]

- Tacitus, Vit. Agric., c. 20, 21. https://www.electricscotland.com/history/wylie/vol1ch16.htm[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vespasian[↩]

- https://roman-empire.net/people/titus/[↩]

- Tacitus‘ The Agricola, along with the many published historical discussions of the campaigns, particularly Cunliffe‘s Iron Age Britain , CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8494910[↩]

- The Votadini were a Brittonic people of the Iron Age in Great Britain. Their territory was in what is now south-east Scotland and north-east England, extending from the Firth of Forth and around modern Stirling to the River Tyne. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Votadini[↩]

- The Selgovae were a Celtic tribe of the late 2nd century AD who lived in what is now the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright and Dumfriesshire, on the southern coast of Scotland. They are mentioned briefly in Ptolemy’s Geography, and there is no other historical record of them. Their cultural and ethnic affinity is commonly assumed to have been Brittonic. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selgovae[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonine_Wall[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Damnonii[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Novantae[↩]

- https://lochmaben.org.uk/go-native/heritage/a-name/[↩]

- https://maps.nls.uk/roy/[↩]

- John Watson, 1770, quoted in The Early Maps of Scotland to 1850. (1973). United Kingdom: Royal Scottish Geographical Society page105.[↩]

- https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/about/history[↩]

- CC-BY (BL) https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=8.4&lat=55.57884&lon=-4.26194&layers=4&b=1[↩]

- Also known locally as Birrens https://canmore.org.uk/event/1017430 and https://canmore.org.uk/site/67099/birrens and https://www.dng24.co.uk/54k-funding-allows-focus-on-roman-hill-fort-site/[↩]

- https://canmore.org.uk/site/66277/woodycastle[↩]

- https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/places/luguvalium/[↩]

- A titulus is a detached segment of rampart[↩]

- A Latin term for an outward curved extension of the rampart and ditch at one side of the gateway into a Roman fort or camp to provide additional defence for the entrance.[↩]

- https://www.transceltic.com/blog/galdus-scottish-king-whose-legend-honored-ancient-monuments[↩]

- https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/places/ladyward/[↩]

- Air Reconnaissance in Britain, 1965-1968 by J.K. St. Joseph in J.R.S. lix (1969) p.108; and Britannia xvii (1986) p.374. https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/places/lochmaben/ and http://canmore.org.uk/site/66286[↩]

- https://canmore.org.uk/site/66277/woodycastle and https://ancientmonuments.uk/125143-woody-castle-fort-lochbank-lochmaben-annandale-north-ward[↩]

- The New Statistical Account of Scotland Volume 4 (1845) https://www.electricscotland.com/etexts/NewStatisticalAccountofScotland04.txt[↩]