Kinnel Mill – a corn mill

Prepared by Robert Togneri, Lochmaben: August 2023

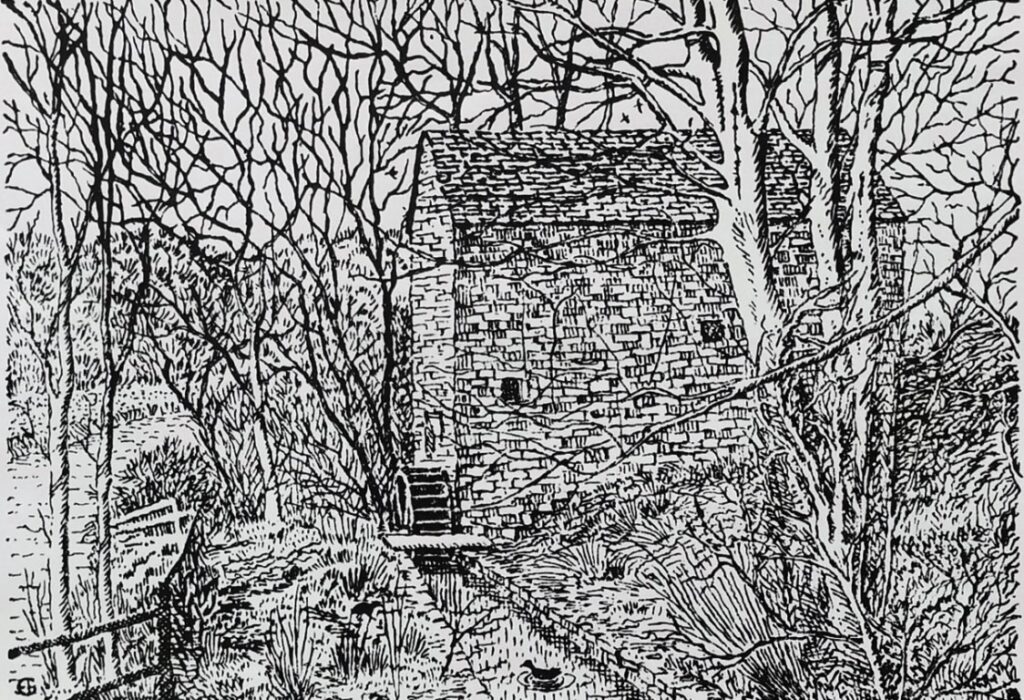

Little information appears to exist about Kinnel Mill, however, the history of corn (or grain) grist mills in Scotland dates back many centuries and is closely tied to the agricultural and economic development of the region. The picture is from an ink print of an artist’s drawing of Kinnel Mill 1

Roman water mills are known along Hadrian’s Wall. However, the first recorded mills appear in royal charters issued to the religious houses in the area.

Some of the mills would have been built as part of the royal estate, whilst others were erected “de novo” by the abbeys. For example, included in the founding charter of the Abbey of Holyrood in 1128 was the gift of the church at Airth.

A confirmation charter by King Robert II 2 provides the detail that the gift included a saltpan, 26 acres, and “freedom to construct a mill in that land” showing that the mill was new. 3

How long a mill existed before it was first mentioned in surviving records is, of course, impossible to determine.

A timeline of references to Corn and Mills

| 1124 | At 14, Robert de Brus, Baron of Annandale, complained that “there was no wheat-bread in Annandale” 7 |

| 1610 | On 15 January after the death of Queen Elizabeth, and the consequent union of the crowns, a feu charter was granted by James VI to George Home, Earl of Dunbar, of the whole of the four towns and the mills (note: plural) of Lochmaben, multures8, the fishings in all the lochs. 9 |

| 1647 | In 1647 the second Earl of Annandale (Johnstone of Thorniequhat) granted a perpetual lease of the castle lands, or “mains of the castle, together with the mill of Hi-tae, fishings, &c., to John Henderson, bailie of Lochmaben, for payment of a certain yearly money rent”3 |

| 1688 | A claim on, and legal battle for, the Mill Lands of Lochmaben. 10 Another claimant to the estate was James Johnstone, described in 1738 as “now of Elshieshields.” He may have been a younger brother of Alexander the twice married, claiming under the last limitation. He certainly had a disposition from his niece Janet in his favour of the Mill lands of Lochmaben: 11 and 12 |

| 1766 | Burgh Mismanagement: Lochmaben Burgh, considered to be one of the wealthiest in Scotland in its time, was taken advantage of by those who held the power whereby they effectively seized (stole?) from the people of Lochmaben some of the commonty – or common lands – thereby diverting income due to the Burgh into these private hands. In particular, the lands including the Lochmaben Mills and mill lands were made over to the Laird of Elsieshiels (the Johnstones), his heirs and successors. Sadly for Lochmaben the earlier ‘theft’ of commonty was never challenged. See 13 and 14 |

| 1776 | In 1776, there is information that suggests that Lochmaben Burgh, considered to be one of the wealthiest in Scotland in its time, was taken advantage of by those who held the power whereby they effectively seized (stole?) from the people of Lochmaben some of the commonty – or common lands – thereby diverting income due to the Burgh into these private hands. In particular, the lands including the Lochmaben Mills and mill lands were made over to the Laird of Elsieshiels (the Johnstones), his heirs and successors. 15 and 16. For more on the “unfair” disposal or appropriation of the “picked parcels” of the commonty’s James Jardine, then late bailie, having refused to accept an acre of Innerfield allocated to him in 1778, the magistrates resolved to dispose of it by public coup—what they ought to have done all along3, sadly for Lochmaben the earlier ‘theft’ of commonty was never challenged. |

| 1785 | 19th March 1785. The entries under this date furnish a striking commentary on the “unfair” disposal or appropriation of the “picked parcels” of the commonty’s. James Jardine, then late bailie, having refused to accept an acre of Innerfield allocated to him in 1778, the magistrates resolved to dispose of it by public coup – what they ought to have done all along. The acre was exposed accordingly, and, after a warm competition, was adjudged to John M’Culloch, at a price, or grassum, of £12 for the acre, (more than £15 imperial measure,) with 3s. of yearly feu-duty. There cannot be a stronger proof than this affords of the mismanagement of the burgh’s affairs. 17 |

Kinnel Mill then and now

The 1766 Plan of Broomhills Commonty, dated 17 May 1766 of Broomhills Common, Lochmaben 18 part of which is reproduced shows a map of Kinnel Water.

The parcel of land on the attached map marked 8, 9 and 10 encompassing the Commonty (Common Land) which included Kiln Hills at numbers 8 and 9 suggests this area was in use at an early age for the drying and ”shilling” of the grain before milling.

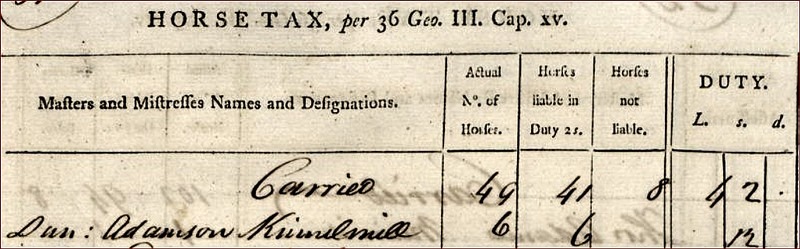

In 1797-8 The occupant of Kinnel Mill was Duncan Anderson who for that year paid a Farm Horse Tax of 12 shillings for the 6 horses he owned all of which were liable to duty. An abstract of the entry is shown below. 19

It can reasonably assumed that these horses were used to pull carts for the transport of goods to and from the mill19. This appears to be the last record of the mill in use and most probably the mill fell out of use between 1798 and 1857.

In August 2023 a visit was made to the site of Kinnel Mill which sits on the banks of the Kinnel Water below the row of cottages now called Kinnelbanks;. The occupants of Kinnelbanks own the mill which is in a sad state of disrepair, it has most likely lain unused since the late 1800s. The mill lade, which can be presumed to be original still exists in part, much of it has been overgrown and filled in with scatter from agricultural use and floods over the intervening decades.

A detailed Ordnance Survey map from 1857 clearly shows a caul once existed in the Kinnel Water this has largely collapsed over time. 20

This caul would have raised the normal water level of the river, allowing it to be diverted into a dug lade which followed the river’s curve to the mill where it would have driven a wooden undershot vertical water wheel.

The map clearly shows the return path for the water flow to re-enter the river after the mill and two further diversionary paths to allow the flow of water to be diverted away from the mill wheel to stop it from turning. There would be gates at that time to turn the flow of water ‘on and off’.

Examining the mill structure itself, from the outside, reveals that the mill, as it now stands, would appear to have been built upon a smaller pre-existing structure. This ‘extension’ would suggest that the mill may, and most likely does, date back to mediaeval times.

The picture of the gable wall, viewed from the river, clearly suggests the structure of a much smaller underlying building, also with a pitched roof. Inset in the centre of this older structure is a bricked-up small square window the purpose of which would be to allow access to the top of the mill wheel.

The extension work carried out, most probably in the mid-18th century would increase the capacity, productivity and profitability of the mill and would possibly coincide with the Johnstones taking ownership of the mill from the commonty. It may be reasonable to assume that improvements were made at that time, but it has not been possible to confirm that theory at this time. It is also likely that the cottages at Kinnelbank (sometimes Kinnel Bank) would be built at that time.

This mill probably fell out of use sometime in the mid-19th century due to increasing challenges from larger, more modern, mills and increasing imports.

In 1857 as part of the Ordnance Survey mapping of this area, three residents were interviewed about the place names 21.

Recorded in the 1857 extract showing Kinnel Mill ownership, the name Kinnelbanks was also recorded at that time as Kinnel Banks with the names being supplied and verified from three local sources. At the same time, the location was verified as “About 1 1/3 mile N.E. by N. [North East by North] of Lochmaben”. Kinnelbanks was described in the entry as “A range of cottages with gardens attached, property of David Johnstone”.

There was a second entry on the extract recording the existence of Kinnel Mill but this was subsequently crossed out. Although no reason is given for this ‘crossing out’ it is reasonable to assume it was done as the mill was no longer used as such and closed before 1857.

- Courtesy of the Mills owners Sarah and Martin Armstrong[↩]

- Robert II (1316 – 1390) was King of Scots from 1371 to his death in 1390. The son of Walter Stewart, 6th High Steward of Scotland, and Marjorie, daughter of King Robert the Bruce, he was the first monarch of the House of Stewart[↩]

- Lochmaben 500 Years Ago: Reverend William Graham 1865[↩][↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bere_(grain)[↩]

- https://baronymill.com/product/orkney-beremeal[↩]

- The farm on the Lockerbie side of Shillahill Bridge was once known as Shilling Hill before the bridge was built over the old ford of the River Annan[↩]

- Robert de Brus at the age of 14 years (The third of that line and direct ancestor of ‘Robert the Bruce’ (seventh of that line), the second of Annandale, lived, as Baron of Annandale, was sent by his father to delivered up to his mother, then at Skelton Castle in North Yorkshire. While in England on this occasion, young Brus had apparently fared better than when at home in Scotland. He had learned, at all events, to relish the southern bread more than the northern oaten cake; and having represented to his father that “there was no wheat-bread in Annandale,” the indulgent parent gave him the lordship of Herts and Hartlepool, in the county of Durham, to supply him with this luxury at Lochmaben. Apparently, the local mills did not produce to his tastes![↩]

- tenants had to pay a proportion of all the grain that they grew[↩]

- 15 January 1610 Feu Charter – to George Home, Earl of Dunbar, one of the gentlemen of his majesty’s bed-chamber, and a great favourite of the king, of the whole of the four towns by name, with two acres called “Amountua,” two acres of “Cuning-hillis,” the lands of“Baillie and Mortlandis,” “Lochma-ben Stane,” the mills of Lochmaben, multures, “quhyte fischingis of Cumertreis,—omnes et singulas piscationes omnium lacuum,” – (the fishings in all the lochs,) and in the “Gairth,” the foggages of “Woodcokhair,” &c.: Lochmaben 500 Years Ago: Rev. William Graham 1865[↩]

- In 1688, Alexander Johnstone was retoured heir on 2 March, he was married twice, but after he died his widow, Janet Carruthers by whom he had two sons, married James Maxwell, of Barncleuch, by whom she had a son, James Maxwell younger of Barncleuch. This second marriage of Alexander Johnstone led to much litigation. The result was a lawsuit between Theodore Edgar and James Maxwell. ((Particulars of which will be found in the printed Information belonging to the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society.[↩]

- Particulars of which will be found in the printed Information belonging to the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society.[↩]

- A History of Dumfries by Robert Edgar (1915) http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028091233 [↩]

- Instead of a revenue of some thousands of pounds a year, which the lands are now worth to the successors of those who got them, the income of this burgh is under £20. As a specimen of ruthless spoliation and improvidence, it has been stated that “at the time Elshieshiells Castle was built, some of the building materials were left unused; and, Lochmaben being without a cross, the Town Council, as the price of these materials for building the cross, made over to the laird of Elshieshiells, his heirs and successors, the mill and mill lands of Lochmaben, part of the burgh property.”: These subjects were in 1845 worth £100 of yearly rent.: Statistical Accounts of Scotland 1845[↩]

- Lochmaben 500 Years Ago: Rev. William Graham 1865[↩]

- Burgh Mismanagement: Instead of a revenue of some thousands of pounds a year, which the lands are now worth to the successors of those who got them, the income of this burgh is under £20. As a specimen of ruthless spoliation and improvidence, it has been stated that “at the time Elshieshiells Castle was built, some of the building materials were left unused; and, Lochmaben being without a cross, the Town Council, as the price of these materials for building the cross, made over to the laird of Elshieshiells, his heirs and successors, the mill and mill lands of Lochmaben, part of the burgh property.” These subjects were in 1845 worth £100 of yearly rent.—(Statistical Accounts of Scotland 1845) (Lochmaben 500 Years Ago: Rev. William Graham 1865).[↩]

- see 17 May 1766 Plan of Broomhills Common[↩]

- Lochmaben 500 Years Ago: Rev. William Graham 1865[↩]

- Plan of Broomhills Common, Lochmaben 17 May 1766 (sic. Legal Theft) https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/image-viewer/maps_plans/maps_plans-12666689_334278_RHP5_PL795?search_token=105569582464e845d75e7d4[↩]

- https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/digital-volumes/historical-tax-rolls/farm-horse-tax-rolls-1797-1798/farm-horse-tax-1797-1798-volume-03/51[↩][↩][↩]

- Extract showing Kinnel Mill location and ground layout from – Survey 1857 https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/record/nls/2048/ordnance-survey-six-inch-to-the-mile-dumfriesshire-sheet-xlii/OS6Inch[↩]

- 1857 Extract showing Kinnel Mill ownership Kinnelbanks aka Kinnel Banks, name(s) given by Mr John Duff, Mr John Beck and Mr James Proudfoot of Templand. [Situation] About 1 1/3 mile N.E. by N. [North East by North] of Lochmaben – A range of cottages with gardens attached, property of David Johnstone – [Page] 38 — Parish of Lochmaben — Plan 42. 11 Trace 6 Kinnelbanks Mill – scored through [Signed] M Donohue https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/digital-volumes/ordnance-survey-name-books/dumfriesshire-os-name-books-1848-1858/dumfriesshire-volume-36/38[↩]