Bruce’s Castle

Lochmaben’s Bruce (Old) Castle

Prepared by Robert Togneri, Lochmaben: March 2024

Ignoring Woody Castle, which is believed to originate from the Iron Age, this is an exploration of Lochmaben’s Old Castle which once sat at the head of what is now Mounsey’s Wynd on the edge of Lochmaben Golf Course. While it will be shown that it is connected to Lochmaben Castle at Castle Loch it should not be confused with the later castle.

Scant information exists regarding the history of these islands before the Roman invasion, and knowledge remains sparse for many centuries after that. Following the Roman withdrawal from Britain, the land was fragmented into numerous kingdoms.

It is believed that Annandale, along with Lochmaben, falls within the confines of the ancient realm known as Strath Clyde, encompassing the region extending northward to the Forth and Loch Lomond. Alcluyd 1, present-day Dumbarton, served as its capital.

Brix – the birthplace of the name Bruce

However, the journey to Lochmaben’s first castle begins in a village that today is called Brix 2, a Commune in the Cotentin Peninsula in Normandy located between Cherbourg and Valognes, whose name has distorted over the centuries.

Numerous testimonies, including a protohistoric wall, prove that the hill of Brix was inhabited by the Romans who established a villa there, i.e., a small administrative centre.

According to the oldest known Latin forms, the name Brix is said to be related to the Celtic Bruga or Old Irish bruig, that is to say, to a piece of land covered with heather or wood. In the Middle Ages, broce or bush was a clump of trees near a feudal manor; and brusc is still the vulgar name of a species of heather.

But the oldest document on the existence of Brix is the account of the translation 3 of the relics of Saint George from Portbail to Brix in 747, which appears in the chronicle of the Abbey of Fontenelle 4, founded in the sixth century by Saint Wandrille.

According to this account, at that time, a small vessel was stranded near the place called the Port of Ballius, containing the remains of Saint George 5, governor of Cappadocia about the year 303, and which was carried by a chariot to the top of a hill, at the foot of which flowed the river Undwa (the Ouve), and where the village of Brutius, which belonged to a powerful man named Benehardus was. To house the relics, he built a church in honour of Saint George and donated it to the Abbey of Fontenelle.

Brix, a parish on the banks of the Ouve, was called Brutius before the Scandinavian invasion 6 in the 9th Century, and its first lord could therefore only take its name.

The “de” in names originates from Norman French and is commonly referred to as a Norman prefix. It signifies “of” or “from” and indicates a place of origin or ancestral lineage. This usage was prevalent among the Norman nobility after the Norman Conquest 7 of England in 1066. Over time, as English evolved, many of these Norman prefixes were assimilated into English surnames or dropped altogether. However, in some cases, they persisted, especially among noble families.

Around the year 1000, Duke Richard II 8 arranged the establishment of the dower for his betrothed, Judith de Bretagne 9, which encompassed Bruet (now known as Brix).

In January 1026, Richard III 10 prepared for the dower of someone who never became his spouse, as he passed away before marrying Adèle, the daughter of Robert the Pious 11, King of France. The text reads: “I, Richard, Duke of the Normans, receive you, Lady Adèle, as my wife in lawful marriage. I therefore grant you as a dower, among the places that belong to me, the city called Constantia (Coutances), with the county, except the land of Archbishop Robert. I also concede to you the castles which are situated there, namely Carusbuc (Cherbourg), that which is called Holmus (Isle-Marie, sur Picauville), that which is called Bruscum, with their dependencies, …”.

Bruscum is identifiable as Brix, reminiscent of the Brutius mentioned in the Fontenelle chronicle, hinting at the eventual evolution into the surname Brus or Bruis, which would later transform into Bruce.

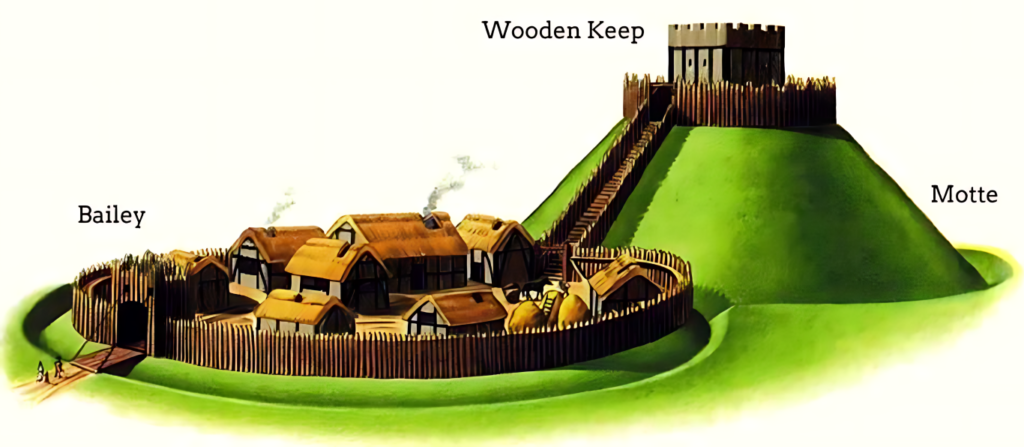

It is likely the castle existing at Brix was a rudimentary wooden tower or keep situated atop a motte, accompanied by a moat and palisade. The emergence of stone castles didn’t occur until the mid-11th Century.

This castle was under the ownership of the Duke of Normandy 12, indicating that the initial lord adopting the name Brus couldn’t have acquired this domain until after 1026, during the reigns of either Robert the Magnificent 13 who passed away in 1035, or his son William the Bastard 14 otherwise William the Conqueror who on April 20, 1042, gave to the church of Cerisy the “…tithe of the deniers of the viscounty of Cotentin, the tithe of the viscounties of Coutances and Gavray, that levied on the mills and the revenues of the forests of Montebourg, Bruis (Brix), Rabey, Cherbourg, Valdecie, Luthumière.

In this text of 1042, Brix is called Bruis and was only to take on its definitive aspect in the following centuries: Bruiz (1325), Bris (1399), and finally Brix.

There can be little doubt, therefore, that the family of Brus owes its name to the village now known as Brix, the preposition de, always attached to the name of the first lords, testifying to the origin. And Bruce is the modern form of the last name.

Who was the first lord of Bruis?

The old stronghold of Brix was given to Robert de Brus I’s kinsman, Adam who built his castle 15 there, perhaps after the family had come to Normandy with the retinue of Matilda of Flanders 16, the Conqueror’s bride.

Matilda is reputed to have been involved in the creation of the Bayeux Tapestry 17 following William’s success at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

The castle was built as a Motte and Bailey 18, a type introduced to France by the Flemish and to England by William the Conqueror.

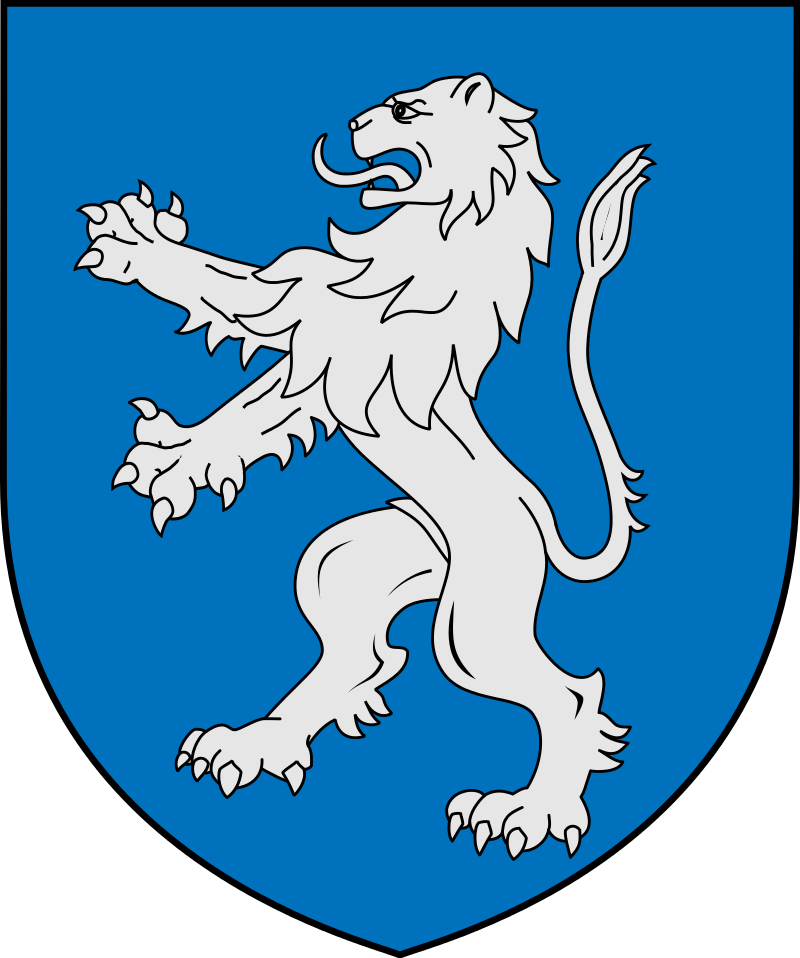

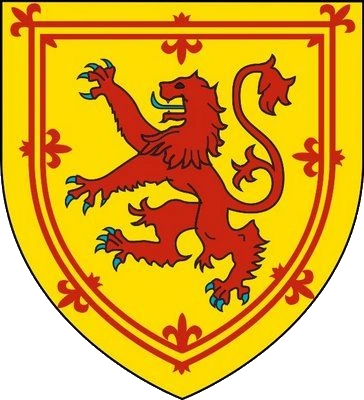

The first arms borne in England by the Bruce family was the Azure (blue) Lion of Leuven, this suggests a connection with Flanders and the Castellans of Brugge.

Count Lambert of Lens 19, the heir of his mother, Maud de Louvain who married Count Eustace I of Boulogne 20. Her cousin Henry’s grandson, Joscelyn, followed Robert de Brus I in bringing the blue lion to England. Robert (later ‘de Bruis’) must have been a younger grandson of Count Lambert I and therefore a first cousin of Maud de Louvain.

When Joscelyn de Louvain 21 came to England to marry the heiress of the Percys, it was natural for Robert de Brus I to yield up the azure lion to him, as the senior representative of the family in Brugge. Robert adopted the device now associated with Bruce and Scotland – the Lion Rampant 22.

The earliest Robert de Bruis may once have been known as Robert de Brugge since a man of that name and title held the castellany from 1046 until he disappeared from Flemish records in 1053. That was the year in which Matilda of Flanders married William, Duke of Normandy. Many nobles of her country attended Matilda into the Duchy, and there is no reason why Robert de Brugge of the princely houses of Louvain and Boulogne should not have been among them.

Emma de Bretagne was a noblewoman from Brittany, a region in north-western France. She was the daughter of Alain IV 23, Duke of Brittany, and became a significant figure through her marriages and alliances. Emma was first married to Alain de Dinan, a Breton nobleman, with whom she had several children. After her first husband’s death, Emma married Robert de Brus I, likely to solidify alliances between their respective families.

Their marriage was part of the intricate web of alliances and marriages that characterized medieval European politics, arranged to strengthen familial ties, secure territories, or consolidate power.

Robert de Brus I was a supporter of William I (1028-1087) and fought alongside him during the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. William was Duke of Normandy (as William II) from 1035 and King of England (as William I) from 1066, one of the greatest rulers of the Middle Ages otherwise known as William the Conqueror.

He made himself the mightiest noble in France and then changed the course of England’s history by his conquest of that country. As a reward for his loyalty, Robert was granted extensive estates in England, including lands in Yorkshire hence the title Lord of Skelton.

Grant of Annandale by David I to Robert de Brus I

Unfortunately, there are no written records about Annandale before 1124, when King David I took the throne. Any valuable documents we might have had, from earlier times or even the next 150 years, were stolen by Edward I of England. Many of which were lost or destroyed.

This lack of records makes it difficult to know for sure who owned Annandale in the distant past. Some believe it belonged to the rulers of Galloway before becoming royal property. In fact, before the 12th century, Scotland only referred to the land north of the rivers Forth and Clyde.

Regardless of whether Lochmaben Castle housed royalty, Annandale belonged to the crown by 1124 when King David I gifted the land to Robert de Brus I, a close friend, and ancestor of Robert the Bruce VII, the future King of Scotland (Robert de Brus was the great-great-great-great-grandfather of Robert I of Scotland).

King David, accompanied by his queen brought into Scotland a large retinue of her Flemish kinsmen. They received large estates in Scotland and introduced a feudal system that soon took the place of the older Celtic way of life. These Flemish knights were the ancestors of many Scottish families – Balliol, Beaton, Brodie, Bruce, Cameron, Campbell, Comyn, Crawford, Douglas, Erskine, Fleming, Fraser, Graham, Hamilton, Hay, Innes, Leslie, Lindsay, Lyle, Murray, Oliphant, Seton, Stewart.

As soon as they could be built, castles, great and small were flung up at every vulnerable point.

Annan Castle

The Bruce family, originally known as the de Brus family, were granted control of Annandale, including Annan Castle, by King David I of Scotland in 1124. This was a strategic move by the king to secure the southwestern border of his kingdom.

The Bruce’s likely built Annan Castle in the early 12th century as a motte and bailey castle. This type of castle consisted of an earthen mound (motte) topped with a wooden tower and an enclosed courtyard (bailey) for additional living and storage space.

Unfortunately, Annan Castle faced challenges. The River Annan flooded in the mid-12th century, eroding part of the castle’s foundation and rendering it unsuitable as the main seat of the Bruce family. After the flood damage, the Bruce’s relocated their primary residence to Lochmaben Castle, situated further north on higher ground and less susceptible to flooding.

Despite their short stay, Annan Castle remains significant in the Bruce family’s history. It marked their early foothold in Annandale and laid the groundwork for their future rise to prominence in Scotland, culminating in the reign of Robert the Bruce V ‘The Competitor’ 4th great-grandson of the first Robert de Brus I to hold Annandale and 7th great-grandson of Robert de Brugge.

Today, the remains of Annan Castle are a scheduled monument and open to the public as a park. While much of the castle has eroded, you can still see the earthwork remnants of the motte and the surrounding area.

Cursed

There are legends associated with Annan Castle, including one about a curse placed on it by a 12th-century Bishop of Armagh, Maolmhaodliog ua Morgair, named (Saint Malachy O’More) who passed through the town on his way to Rome about 1138.

He stayed with Robert the Bruce VII as his guest. During the stay, he overhead servants talking about a robber who was awaiting a sentence of death. Malachy asked Bruce to spare the life of the man. Bruce said he would and Malachy blessed the Bruce household.

When leaving, he saw the robber hanging from the gallows in Annan and, in anger at the deceit, Malachy laid a curse on Bruce, his family, and the little castle hamlet of Annan. After Malachy died in 1148, Robert paid for lights to be maintained at the shrine of Saint Malachy at the monastery of Clairvaux, France, where the soon-to-be saint had died. Folklore has it that Malachy’s curse was never expiated.

The story goes that soon after flooding swept away a large section of the motte bringing down part of the castle, resulting in the Bruce’s moving to Lochmaben.

Ever since the 12th century, the Bruce’s considered themselves cursed. Robert de Bruce VI, father of King Robert I believed his contracting leprosy was ‘the finger of God upon me’ and a consequence of the family’s execration.

Lochmaben’s Bruce Castle

The importance of Lochmaben lies in its strategic position. Due to forest and marsh, a traveller to Scotland from Carlisle found it necessary to travel up Annandale and then branch off either westwards for Galloway or north-east for Edinburgh. In either event, it was necessary to travel first as far as Lochmaben.

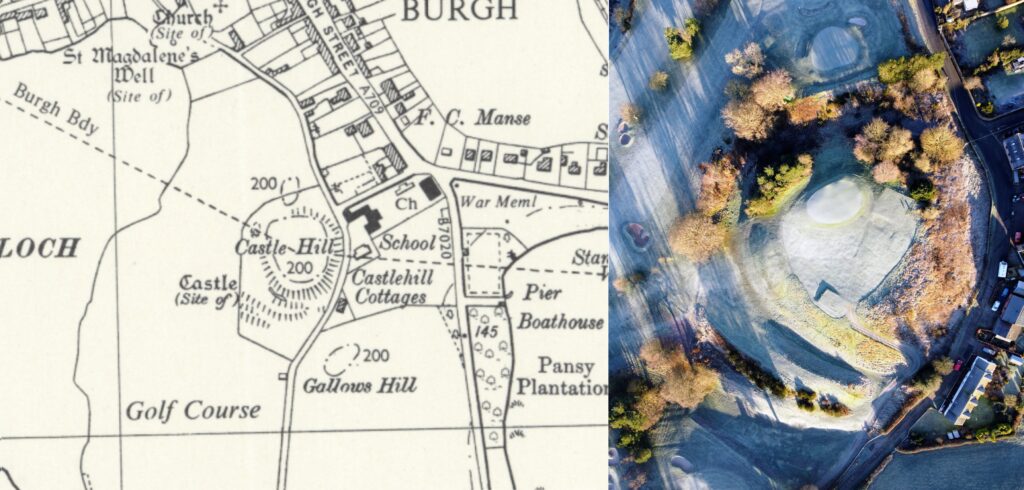

It is not surprising therefore that, when the Brus family motte was destroyed by the river at Annan, the Brus moved his stronghold to Lochmaben. The date of the bailies construction is not known, but the Motte was recorded as in existence in 1166 and in 1173 when William the Lion held the ‘castle’ of Lochmaben 24.

It became the caput of Annandale by 1204 and the last mention of it is in 1315-21 when King Robert I granted the lands of Mouswald to Thomas de Carruthers-the reddendo 25 being a pair of gilt spurs to be delivered “apud manerium nostrum de Lochmaben” (lit: at our manor of Lochmaben).

It is possible that King Edward stayed here on 4th-5th September 1298.

The original castle of Lochmaben stood between the Castle Loch and the Kirk Loch, upon a natural eminence, of from twelve to fourteen acres, close to the town, a well-chosen spot, overlooking a great expanse of country, and from which, notwithstanding the thick forests which then surrounded it, the motions of an enemy could be easily watched.

The town likely owes its origin to the choice of this site for a stronghold, just as the city of Edinburgh does to its fortified rock. Besides others who might find it convenient to live near it for protection in times when “might was right and right was might,” the inhabitants were originally the villeinage or retainers of the chief to whom the castle belonged, having a portion of land assigned to them in common, for their military and praedial services.

This ancient fortress was surrounded by deep dry moats, still distinctly traceable. The fortress was initially supplied by water from a spring nearby but a greater supply was piped in from the rising grounds near where St Thomas’s Chapel stood about a mile and a half to the west, on the A709 Dumfries Road, in leaden pipes.

In the early to mid-1800s three pieces were revealed, one within the present enclosure at the south-west corner, the other in the adjoining park, and the third while a ditch was being cut through a moss, about midway between the castle and the spring. That spring still discharges a supply of pure water on the farm of St Thomas; (now Hunter House Farm) and close beside it there is another fountain called the Baptism Well.

It is also said that there was an orchard planted on the slope from the castle down to the Kirk Loch.

The Brus motte at Lochmaben stands now on the golf course and has been much altered by subsequent landscaping. As a result of tee-building operations on Lochmaben Golf Course in November 1966, 27 fragments of pottery with fragments of heavy unglazed tile, oyster shells, and animal bone were recovered. These were dated to the late 12th-early 13th century.

Finds of medieval pottery and tiles suggest that it continued in occupation into the 14th century 26. Probably it remained in use until the stone castle on the loch replaced it.

The image shows the site of Bruce Castle as mapped in 1888, side by side with an aerial photograph from 2023. The site lies on what is now called Kirk Loch Brae, opposite its junction with Mounsey’s Wynd. It is important to remember that Lochmaben was a vital nexus for the area, being on the main road from England in the south, Galloway in the west, Strath of Clyde in the north and Edinburgh to the northeast.

This traffic would pass through the historically named Castlehillgate to the north west, and journeys to the south would travel past the Gallows Hill which in ancient times was known as Gallows Knowe, on which, in ancient times, stood formidable gallows, seldom seen during the Border wars without the dangling appendage of one or two reivers. Continuing south, travellers would pass Castlehill Farm to Vendace Burn and on towards Hightae past the future site of a castle to be built by Edward I.

The baronial courts of Lochmaben, and even occasional warden courts, were probably held on the summit of Castle Hill, whence the judges beheld their sentences promptly carried into execution. While men would be hung from the gallows, the punishment inflicted upon female convicts was, universally, drowning; and in cases of very heinous crimes, such as witchcraft where witches would be burned at the stake. It was deemed highly indelicate and shocking to expose females to any other mode of execution. Women faced the cukpule or cockpool for ducking or drowning women convicted of crime. There are two suggested locations for Lochmaben’s cukpule. The first was a deep pit within the ditch of the castle on the north-west, on which the Peel stood, on an ancient map the surveyor has written the word “fosse,” which, in old Scotch, signifies a “pit for drowning.” The second location is thought to be Grummel Loch (now Grummel Park) 27.

Below is an 1832 Sketch by James Skene 28 of Lochmaben ‘Old Castle’ with Castlehill Cottage and Burnswark in the background.

One of the first moves of Edward I at the start of the War of Independence was to gain control of the major strategic points in the Lowlands, notably Berwick, Stirling, Bothwell and Lochmaben. The campaigns of 1298 resulted in the capture of a number of these, including Lochmaben, where work was set in hand by Sir Robert de Clifford on the building of a peel or palisade.

Eight carpenters, 4 sawyers and 48 workmen were employed on the task and were sent from Carlisle under the protection of 26 crossbowmen. This, the first peel at Lochmaben, was almost certainly constructed on the site of the later stone castle. The first peel was defended against the Earl of Carrick in 1299, but the siege resulted in orders being given for the defences to be increased 29. In 1301 the Constable reported that ‘7000 Scots had burnt our Pele toun and assailed our Pele’. It is probable the peel remained nevertheless in English hands until 1306, when it may have briefly fallen to Robert Brus before surrendering to the Prince of Wales in that year.

The fortunes of war changed again, and it would appear that Lochmaben was held by the Scots until 1333, when once more it reverted to the English. Although there are references to Scottish attacks on it during the 14th century, it seems probable that it remained in English hands until finally reverting to the Scots in 1385. 30

What is a motte and bailey?

A motte-and-bailey castle is a simple but effective type of early medieval fortification. Modern research into the Scottish mottes began in the 1890s when they were classified as Norman. However, their construction is more similar to that of Flanders which as shown had clear Flemish connections with Normandy.

As in Flanders, the royal castles were most often to be found in towns, places which could be quickly fortified and named as Burghs 31.

Lochmaben is one of the oldest royal burghs, it became a ‘defacto’ Burg or Burgh early in the 12th century believed to have been made such by Robert de Brus I. This approach was borrowed directly from Charlemagne 32 who reigned from 768 to 814 and whose lineage can be traced through Flanders directly to Queen Maud (Matilda) 33 the wife of King David I. Charlemagne called his fortified centres ‘burgs’ 34.

Many of the ‘motte and bailey’ castles were likely built by Flemish craftsmen.

Here’s the breakdown:

- Motte: A large, raised earthwork, often artificial. It could be built from scratch or incorporate a natural hill.

- Bailey: An enclosed courtyard next to the motte, sometimes surrounded by a ditch for added defence.

On top of the motte, there would typically be a wooden tower called a keep, which housed the lord and his family. The bailey would contain workshops, stables, and living quarters for soldiers and servants.

These castles were known for being:

- Quick and easy to build: They used mostly wood and earth, requiring minimal skilled labour.

- Effective defence: The high motte provided a good vantage point and offered protection from attackers.

Motte-and-bailey castles were popular, from the 10th to 13th centuries in Europe. However, many were developed relatively quickly into stronger stone castles.

Bruce name forever

The Bruce surname is renowned in Scottish history, hailing from Normandy the first known Robert de Bruis in England fought alongside William the Conqueror in 1066. His son, also Robert, ventured to Scotland with King David I in 1124, receiving lands in Annandale. Robert, the seventh Lord Annandale, became King in 1306 after a series of familial and political alliances.

Scotland’s long struggle for independence began, undertaken by William Wallace, who was arrested and executed, then pursued by Robert the Bruce VII, the competitor’s grandson. Crowned in 1306, Robert the Bruce was hunted down for a long time as a thief.

It took an extraordinary tenacity to win back his country, by a mixture of cunning and audacity, until his victory at Bannockburn in 1314, which drove the English out of Scotland. Robert Bruce died in 1329 and was succeeded by his son, King David II, who disappeared in 1371 without posterity.

His victory at Bannockburn in 1314 secured Scotland’s independence. After King Robert’s son died without heirs the Bruce lineage continued through his daughter Lady Marjorie Brucewho married Walter Stewart, the Steward of Scotland 35, their son succeeded David and was the stem of the famous Stuart family.

Though not technically a clan, the Bruce’s are a significant lowland family, with the present Earl serving as Chief.

- ‘Dumbarton Parish Church History – Dumbarton Riverside’. Accessed 18 March 2024. Dumbarton – Alcluyd.[↩]

- ‘Brix, France (Manche, Normandy): Tourism, Attractions and Travel Guide for Brix’. Accessed 9 March 2024. Brix.[↩]

- ‘Reliques de Saint Georges Arrivées Miraculeusement à Portbail, et Miraculeusement Transportées à Brix – Le50enligneBIS’. Accessed 9 March 2024. Portbail.[↩]

- ‘Abbey of Saint Wandrille’. In Wikipedia, 3 March 2024. Abbey of Saint Wandrille.[↩]

- ‘George Of Cappadocia | Saint, Martyr, Patriarch | Britannica’, 6 March 2024. George of Cappadocia.[↩]

- Short history website. ‘Vikings in Early European Medieval History’, 11 April 2017. Scandinavian Invasion.[↩]

- BBC Bitesize. ‘The Norman Conquest – KS3 History’. Accessed 18 March 2024. The Norman Conquest.[↩]

- ‘Richard II, Duke of Normandy’. In Wikipedia, 8 January 2024. Richard II.[↩]

- ‘Judith de Bretagne, Duchesse de Normandie († 17 Juin 1017).’ Accessed 18 March 2024. Judith de Bretagne.[↩]

- ‘Richard III, Duke of Normandy’. In Wikipedia, 20 February 2024. Richard III.[↩]

- ‘Robert II | Capetian Dynasty, Holy Roman Emperor, Reformer | Britannica’, 8 March 2024. Robert II King of France.[↩]

- ‘Duchy of Normandy’. In Wikipedia, 5 March 2024. Duchy of Normandy.[↩]

- ‘Robert the Devil, Also Known as “the Magnificent”’. Accessed 18 March 2024. Robert the Magnificent.[↩]

- History Hit. ‘William the Bastard: The Norman King’s Traumatic Early Years’. Accessed 18 March 2024. William the Bastard[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ch%C3%A2teau_de_Brix.[↩]

- Historic UK. ‘Matilda of Flanders’. Accessed 18 March 2024. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Matilda-of-Flanders/.[↩]

- ‘The Bayeux Tapestry and Matilda of Flanders – History of Royal Women’. Accessed 20 March 2024. https://www.historyofroyalwomen.com/matilda-of-flanders/bayeux-tapestry-matilda-flanders/.[↩]

- https://historyforkids.org/motte-and-bailey-castle-facts-and-information/[↩]

- ‘Lambert II, Count of Lens’. In Wikipedia, 9 November 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Lambert_II,_Count_of_Lens&oldid=1184308226.[↩]

- ‘Eustace I, Count of Boulogne’. In Wikipedia, 13 March 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Eustace_I,_Count_of_Boulogne&oldid=1213518900.[↩]

- ‘Joscelin of Louvain’. In Wikipedia, 13 June 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Joscelin_of_Louvain&oldid=1160002772.[↩]

- Historic UK. ‘The Flags of Scotland – Saltire and Lion Rampant’. Accessed 18 March 2024. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofScotland/The-two-flags-of-Scotland/.[↩]

- ‘Alan IV, Duke of Brittany’. In Wikipedia, 8 March 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alan_IV,_Duke_of_Brittany&oldid=1212520544.[↩]

- Anderson, Allan Orr. Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers, A.D. 500 to 1286. London D. Nutt, 1908. Page 247 http://archive.org/details/scottishannalsfr00andeuoft.[↩]

- ‘Definition of REDDENDO’ – a clause in a charter specifying the particular duty or service due from a vassal to his superior. Accessed 18 March 2024. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/reddendo.[↩]

- Truckell, Alfred E. ‘Medieval Pottery in Dumfriesshire and Galloway’. Transactions of the Dumfries and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society XLIV, no. Third Series (1967): 133, 154–55. https://dgnhas.org.uk/sites/default/files/transactions/3044.pdf#page=152.[↩]

- Graham, Rev William Graham (of Edinburgh). Lochmaben Five Hundred Years Ago, Or Selections, Historical and Antiquarian. W.P.Nimmo, 1865. https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Lochmaben_Five_Hundred_Years_Ago_Or_Sele/qqYHAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.[↩]

- ‘1832 Sketch by James Skene of Lochmaben “Old Castle”’. Accessed 19 March 2024. https://canmore.org.uk/collection/178055.[↩]

- Great Britain. Public Record Office, Joseph Bain, and Great Britain. General Register Office (Scotland). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland Preserved in Her Majesty’s Public Record Office, London. Edinburgh: H. M. General Register House, 1881. Page 283-284 http://archive.org/details/calendarofdocume02grea.[↩]

- MacDonald, A, and Lloyd Laing. ‘Excavations at Lochmaben Castle, Dumfriesshire’. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 106 (30 November 1975): 124–57. https://doi.org/10.9750/PSAS.106.124.157.[↩]

- ‘BURGH Definition and Meaning | Collins English Dictionary’, 24 March 2024. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/burgh.[↩]

- Biography. ‘Charlemagne Biography’, 24 August 2019. https://www.biography.com/royalty/charlemagne.[↩]

- ‘Maud, Countess of Huntingdon’. In Wikipedia, 10 November 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Maud,_Countess_of_Huntingdon&oldid=1184478875.[↩]

- ‘Burg | Etymology of Burg by Etymonline’. Accessed 24 March 2024. https://www.etymonline.com/word/burg.[↩]

- ‘Stewart, Sir Walter | University of Strathclyde’. Accessed 18 March 2024. https://www.strath.ac.uk/studywithus/centreforlifelonglearning/genealogy/geneticgenealogyresearch/bannockburnprojectdocumentary/stewartsirwalter/[↩]