Lochmaben Health – Who Cares?

By Robert Togneri & Zena Forbes, Lochmaben, October 2023

Mahatma Gandhi once said

“The true measure of any society can be found

in how it treats its most vulnerable members.“

We may consider ourselves fortunate for the place and times we live where some, fortunately the majority, but sadly not all, enjoy reasonable health and prosperity. This article will attempt to plot a journey of care and compassion in the local context before reaching Lochmaben Hospital.

The church has always played a role in the lives of the Scottish population. Among its responsibilities were education, recording of births, deaths, marriages and disciplining errant parishioners for offences such as drunkenness, swearing, Sabbath-breaking and sexual misdemeanours.

The beginnings of poor relief

In medieval times social welfare, including poor relief, was carried out by hospitals maintained by monastic or burgh institutions. Supporting the poor was seen as an act of Christian charity.

The Scottish Parliament and Privy Council made many statements and declarations relating to the problems of the destitute and the ill. Rather than advocating support for the poor in general, these concerns usually came from a desire by the landowning class to maintain a stable society and keep their lands under cultivation by their tenants and cotters.

Legislation addressing support for impoverished individuals began in the 15th century within the context of Parliament. Initially, these laws aimed to tackle the issue of idle beggars. However, two principles gradually emerged over time:

– first, each parish was responsible for caring for its own impoverished residents, and

– second, only specific “categories” of impoverished individuals qualified for aid.

These principles were firmly established by a statute in 1579, which served as the cornerstone of Poor Law until 1845.

In 1425, on 12 March Perth Parliament1, before King James I, set a distinction between able-bodied beggars and those unable to earn their own living.

No one between fourteen and seventy years of age could beg unless the town council decreed they were unable to make their living in other ways, whereupon they would be given a “token” from the aldermen and bailies in the burghs.

The penalty otherwise was “under pain of burning on the cheek and banishing from the country“.

Children were not immune from a precarious existence; if their parents were unable or unwilling to find work then they became vulnerable to starvation and homelessness.

The Kirk Session and Poor Relief

In 1560 following the Scottish Reformation2 the religious hospitals in monasteries were largely abandoned. The Reformed Kirk was concerned about the poor from both a religious and moral sense.

The First Book of Discipline3 declared that each parish should care for its own poor; at least those such as widows, the elderly and those whose age or disabilities left them unfit to work.

Kirk Sessions4 were also responsible for supporting abandoned babies. The shame of conceiving out of wedlock and the harsh realities of poverty meant that many illegitimate children were left to be brought up by the parish.

The demand for financial support at times resulted in a lack of poor relief funds and the Kirk Session were often anxious to locate the parents, as much for the child’s sake as for monetary reasons.

In 1575, 1579 and 1592 Poor Law(s)were passed by Parliament, harsh laws to control the administration of help to the growing numbers of poor people. This increase had been caused by a rising population and repeated food shortages. The Acts said an able-bodied poor person who refused to work should be “whippet and placed in stocks”.

The 1575 Act required parishes to create “a competent stock of wool, hemp, flax, iron and other stuff” for the poor to work on. It also created houses of correction where recalcitrant or careless workers could be forced to work and punished accordingly.

The 1579 Act added the twin aims of ‘the puyr aiget and impotent personis sould be as necessarlie prouidit for’, and that ‘vagaboundis and strang beggaris‘ should be ‘repressit‘.

This Act allowed any heritor to take a pauper child aged between five and 14 into his service; girls had to remain until they were 18 years old and boys until they were 245.

These statutes had two main goals: to ensure necessary support for “the poor, aged, and infirm individuals” and to suppress the activities of “vagabonds and unfamiliar beggars.”

Those eligible for assistance, whether due to age, illness, or other circumstances, had to turn to the last parish where they had lived for seven years or alternatively to the parish of their birth.

Summary of the Poors Law

Overseers of the Poor in each parish.

Compulsory Taxation on parishioners to fund relief for the poor.

Workhouses and Apprenticeships to provide employment for the able-bodied poor and to house the destitute.

Vagrancy Laws making it illegal for able-bodied individuals to beg for alms.

Settlement Laws introduced the concept of “settlement,” meaning that individuals were only eligible for poor relief in their parish of legal settlement.

Limited Relief for the deserving poor, which meant aid was limited to those considered “worthy“. Unmarried mothers, for example, were sometimes treated harshly under this law.

Lochmaben Town Hall once had Jougs6, a metal collar formerly used as an instrument of punishment in Scotland, on the wall to the left of the front door.

The responsibility for caring for the poor in Scotland largely fell on parish authorities7, particularly the Kirk Sessions8 and the heritors9. Parochial councils10 had a role in shaming the sons and daughters of the poor to encourage them to labour hard to support their parents, and to avoid the disgrace of being told that they were upon the poors’ roll. Typically, parishes relied on church collections, income from rented seats, charitable donations, and various funding sources.

This system worked well in rural areas but was insufficient for the rapidly growing industrial towns of the early 19th century, where poverty was concentrated in crowded slum neighbourhoods. Moreover, during the Industrial Revolution11 and frequent trade downturns significant numbers of able-bodied individuals were left without access to poor relief. Additionally, the church-based system faced challenges due to many people having seperated from the established church.

In 1599, the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow12 was founded. It included not only physicians and surgeons but also apothecaries and barbers who commonly attended the sick, the latter were dropped from inclusion in 1722 as surgeons rose up the social scale. The faculty became royal in 1909 and a college in 196213. By the 1830s, Scotland produced more doctors than could be absorbed into civil society, the army or the navy. This might explain why NHS expenditure per person and the ratio of doctors and nurses per person are both higher in Scotland than in England.

In 1793 Reverend Andrew Jaffray wrote14 about the State of the Poor in 1755, Lochmaben, were a population of “1395 inhabitants” had “3000 Souls”. It was common for the head of the house to be listed as ‘the’ inhabitant, spouses and other family members are among the ‘souls’. Among these are 30 on the roll, who are served quarterly out of the public charity, with “but a small pittance to each, there being no fund or provision made for their support, save what is collected in the church“. This number of people considered poor remained relatively stable with 34 recorded in 183515.

“Those that are able are allowed to beg from door to door, many strollers and idle vagrants suffer to travel in the country, with which it is greatly oppressed, and by this, the poor of the parish are robbed of that charity which properly belongs to them“.

The school had a role in tackling poverty. In 1726 James Richardson16, Esq, Merchant of Reading, England, mortified17 in his will the sum of £40018) in the following manner, viz. £200 to the grammar school of Lochmaben; the interest of it to be paid to the master, under the obligation of teaching 10 poor scholars of the parish of Lochmaben English, Latin, Writing, and Arithmetic, gratis:

Another £100 for supporting a library, and keeping in repair a good house, built by the said Mr Richardson, for the use of the schoolmaster, and for preserving, supplying, and continuing the said library: And the interest of the last £100 to go for a school in Hightae, for the benefit of the whole Four Towns19.

Jaffrey comments on the character of the People in his report. “In this burgh and parish, no doubt, a considerable quantity of ardent spirits is consumed: but in general, the inhabitants are sober, industrious, religious, and many of them of considerable intellectual attainments”. He goes on to state that within the last forty years, improvements have taken place in regard to the comfort of Burgh inhabitants both in houses and in clothing.

On leisure in the community, he comments that the prevailing game in summer is quoits, played by many with great dexterity, while in winter curling, of which the parishioners of Lochmaben have long been celebrated and unrivalled.

The local diets were also supplemented somewhat by poaching, which “prevails to an alarming degree, both in game and in the salmon fisheries“.

In 1835 there were “upon the poor roll” 34 persons and a considerable number who occasionally received relief. There were four blind persons, and four deaf and dumb in the parish; one of the blind only receives aid from the poor funds.

In the report compiled by the Reverend John Gardiner))Parish of Lochmaben, Presbytery of Lochmaben, Synod of Dumfries: The Rev. Thomas Marjoribanks, Minister drawn up 1835, while the incumbency was vacant, by the Rev. John Gardiner, a native of Lochmaben. 1835 Page 381)), the use of language, as exemplified in the following paragraph, demonstrates a disdain for the poor and elderly. One would like to believe that it is better today.

“The sum disbursed in 1834 amounted to £81, 10s. 7d20., of which one fatuous21 person received £1022, and some old and feeble individuals £423 each”.

The funds were raised from a number of sources; the weekly collections from parish congregations average nearly 16 shillings24), added to the income from the proclamation of marriages, mortcloth25 dues, and fines inflicted for immoral conduct and irregular marriages – between 1855 and 1874 there were 320 children born with no father26 listed in available records and the fine was 40 shillings27). A further records 68 exist where single mothers took the fathers of their children to the Sheriff Court for child support.

Between 1855 and 1874 there were 320 children born with no father26 listed in available records. A further 68 records exist where single mothers took the fathers of their children to the Sheriff Court for child support.

The Poor Law (Scotland) Act of 1845 introduced Parochial Boards in rural and urban areas and a central Board of Supervision in Edinburgh. This system aimed to collect funds to help the poor but had not been universally adopted by 1860.

Parochial Boards built Poorhouses, as they were known in Scotland whilstcalled Workhouses in England, for certain groups of paupers who did not receive cash allowances, often forming joint “Combination Poorhouses” with other parishes.

The board for Lochmaben, however, decided to build a Poorhouse.

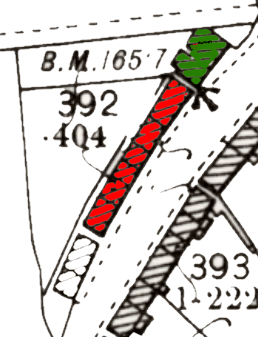

They chose as their site a place on the extreme limits of the Royal Burgh on its north-most point at “Bogle Hole” where, in 1851, they opened the Burgh’s Poorhouse (location shown by arrow on the map28).

Once the house was built, a cast iron plaque was affixed to the building, leading to the renaming of the area as Marjorie Banks New Town, which replaced the less attractive sounding Bogle Hole.

A study of the Ordnance Survey 25-inch map for 189229)) reveals the building pictured at the end of a row of smaller buildings. The building coloured in green is slightly separated from the row of six buildings to the south of it coloured in red. This was the home of the Poorhouse wardens and staff. The last remaining staff were an elderly couple and the Poorhouse finally closed in the 1940s after the Second World War, at that time it had one remaining inmate, an elderly blind man30).

The map shows six terraced buildings adjoining it. Given that segregation of males, females and children was employed, it is likely that these once formed the extent of the Poorhouse. The building immediately adjoining the warden house was possibly a communal food hall.

Over time, the government granted boards more authority, including oversight of vital records and public health matters.

This led to Poorhouses developing more and becoming a place for the sick and infirm to seek limited medical help.

Lochmaben’s former Poorhouse31 is currently (2023) under renovation and extension – the end of the white cottage32 in the second photo is the only other remaining part of the Poorhouse estate.

Poorhouse Operation33Within the Poorhouse inmates were classified as follows:

Males above the age of 15 years

Boys above tne age of 2 years, and under 15 years

Females above tne age of 15 years

Girls above the age of 2 years, and under 15 years

Children under 2 years of age

Segregation of inmates, particularly of males and females, was also enforced. For paupers entering the Poorhouse, life was strictly regulated. There was a prescribed daily routine and work was expected to be performed by inmates according to their capabilities.

To the rear of the property the land was a small comunal farm of runrigs34 to be worked.

Inmates were required to wear the Poorhouse uniform and conform to the Scottish Poorhouse Rules35. An inmate’s own clothes were “purified” by steaming them for three hours and then placing them in a store until the inmate left the Poorhouse.

Poorhouse Clothing typically included under and outerwear, with two of any items such as shirts and stockings that would need regular laundering. Each Item would be marked With the outfit’s identification number and also to identify as Poorhouse property, so discourage theft.

The provision of workhouse clothing served a number of practical purposes.

– It prevented an infestation, such as fleas, that the inmate might be carrying from being carried into the Poorhouse.

– It ensured that the inmate was suitably attired for work or whatever else was appropriate for their situation.

The clothing was not intended to be degrading or denumanising. It did, however, provide a simple control mechanism over inmates’ movements: leaving the workhouse in uniform without permission would constitute theft of property and could lead to an appearance before the magistrates and a possible sentence to prison with hard labour.

The Poor Law Commissioners anticipated that workhouse inmates would make their own clothes and shoes, providing a useful work task and a cost saving. However, they probably failed to realise the level of skill required to perform this and uniforms were more usually bought-in.

The inmates’ clothing, particularly the men’s, was usually made from fairly coarse materials with the emphasis being on hard-wearing rather than on comfort and fitting.

The Poor Law Commissioners decreed that the clothing was to be made out of ‘such materials as the Guardians may determine‘ and ‘need not be uniform either in colour or materials.’

For the men this consisted ot jackets ot strong ‘Fernought36’ cloth, breeches or trousers, striped cotton shirts, cloth cap and shoes.

For women and girls, there were strong ‘grogram37’ gowns, calico shifts, petticoats ot Linsey-Woolsey material, Gingham dresses, day caps, worsted stockings and woven slippers.

Male inmates were usually kitted out in jackets, trousers, waistcoats and some kind of hat, such as a flat cap or a Breton cap.

The inmates’ diet was also prescribed. For working adults, this comprised.

Breakfast – Meal, four ounces; and broth, three-fourths pint imperial.

Dinner – Bread, eight ounces; broth, one-and-halt pint imperial; and boiled meat, four ounces.

Supper – Meal, four ounces; and broth, three-fourths pint imperial

Inmates were bathed once a week, under supervision, in water between 88 and 98 degrees Fahrenheit (31-36⁰C).

Children under fifteen had their hair regularly cut to keep the length at two inches for boys and three inches for girls.

Board of Supervision poor relief appeals

The Board of Supervision was established under the 1845 Poor Law Act. One of its tasks was to hear appeals by paupers against inadequate poor relief granted by Parochial Boards. These appeals were recorded in the Board of Supervision minutes. Cases were often heard over an extended period.

The minutes may contain a variety of information, including about other family members, medical conditions and other circumstances. The following table identifies some of the past residents of Lochmaben Poorhouse who lodged appeals but were unsuccessful. Of the non-residents also found not one has had a successful appeal.

| Name | Year | Deliverance |

|---|---|---|

| James Moffat | 1855 | Refused (poorhouse) |

| David Wilson | 1855 | Refused (poorhouse) |

| Widow Mary Mundell or Williamson | 1863 | Refused (poorhouse) |

| Mary King | 1870 | Refused (poorhouse) |

| Widow Jean Mcgowan or Beck | 1873 | Refused (poorhouse) |

| Widow Mary Tweedie | 1878 | Refused (poorhouse) |

| Andrew Forrest | 1880 | Refused (poorhouse) |

| William Forrest | 1880 | Refused (poorhouse) |

| William Richardson | 1882 | Refused (poorhouse) |

In 1894, these boards were replaced by elected Parish Councils, but their functions remained similar. In the 1920s, during an economic downturn, the rule denying relief to the unemployed was dropped through the Poor Law Emergency Powers (Scotland) Act of 192140. Parishes then started maintaining separate records for different types of relief requests, distinguishing between ‘Ordinary‘ and ‘Able-Bodied‘ applicants.

The parish-based system had flaws, including inconsistent relief levels and disputes between parishes over supporting specific paupers. To address this larger authorities were established to standardize practices and distribute the burden of poor relief more fairly.

In 1930 parish councils were abolished under the Local Government (Scotland) Act of 192941. Thereafter, the responsibility for poor law administration was transferred to county councils, major towns and the cities, which operated through Departments of Public Assistance (or Public Welfare).

This arrangement remained unchanged until 1948 when the existing poor law system was replaced nationally, laying the foundation for what we now call ‘Social Security42’ under the National Insurance Act of 194843.

Nevertheless, various welfare functions continued to be overseen by local authorities, including services for the homeless, elderly care facilities, support for individuals with disabilities, and various services related to children, such as adoption and fostering. These functions, among others, underwent restructuring in 1968, coming together to establish the Social Work Departments as outlined in the Social Work (Scotland) Act of 196844.

Lochmaben Hospital45

1889 – The Local Government Scotland Act of 1889 saw the appointments of Medical Officers of Health46 in areas. Local officials considered that ‘Fever Hospitals’ facilitated control and reduced the spread of disease, which in Victorian times found a fertile breeding ground in overcrowded, unsanitary homes, particularly in towns, which had expanded following the Industrial Revolution47.

Fever hospitals were soon established in Langholm, Annan, Thornhill and Lochmaben. These hospitals were seen as essential in keeping ‘fever‘ patients isolated from general medical care to reduce the spread of disease.

It was considered that capacity would be about 1 bed per 1,500 people. Local units were recommended. Two hospitals were recommended for the area. Lochmaben would be built to serve Dumfriesshire as would Parkhead in Dumfries.

1906 Plans were developed by Frank J.C. Carruthers, F.R.I.B.A48, of Buccleuch Street, Dumfries, an architect who had formerly practised in Edinburgh and came to reside at Lockerbie.

1907 Lochmaben has a Fever Hospital! – ironically, one of the first buildings, the hospital administration building (see photo) and matron’s quarters is the last part still standing (2023). Demolition is scheduled to take place soon to allow housing development.

The layout was standard for fever hospitals, however there were three fever blocks rther than the more usual two. The administrative building was the patient’s point of admission to the hospital complex.

The patient pavilions were of a temporary nature and constructed of iron and wood. The internal walls and partitions were finished in cement to avoid seams, a notorious resting place for microbes, and the whole finishings were carefully designed to avoid acute angles on which dust might gather.

The hospital complex was built outwith, the then, Lochmaben Burgh boundary next to the Dumfries Road behind the building that is the current Lochmaben Hospital. The Ordnance Survey map from 194949 gives a good idea of the scale of the whole complex as does the aerial photograph from the 1950s50 with the main administartion block on the left of the picture.

From the outset, the hospital was designed with infection control in mind. The living quarters of servants and general staff were kept away from those of the nurses.

This arrangement ensured nurses coming from each of the separate treatment pavilions (Diptheria, ScarletFever, Tuberculosis) would not be required to enter either the kitchen annexe or the administrative block. Instead, they passed along an open passage drawing their rations from a service window without entering the kitchen or coming in contact with nurses from any of the other blocks.

1908 The formal opening of the new county fever hospital, Lochmaben Combination Hospital, took place on Saturday, 16th May 1908, at 3.00 pm. The ceremony was performed by Lady Ethel Buchanan-Jardine of Castlemilk51.

The first patient was admitted to Lochmaben Combination Hospital nine days later on 25 May 1908 suffering from typhus. After 4 days, she died. However, the second patient, Mary Graham (photo), aged 4, was admitted with diphtheria on 2 July 1908. She remained for three weeks.

In her mid-teens, she went to work as a cleaner at the fever hospital and was given lodgings in a room in Highfield, a staff house. She later became a nurse.

In the years between the wars diphtheria, meningitis and scarlet fever had a high mortality rate. As their incidence diminished with the advent of vaccines to prevent diphtheria and antibiotics to treat meningitis and scarlet fever, the need for beds to treat these ailments became less.

Christopher William Clayson M.D., F.R.C.P.Ed., D.P.H (1903-2005)

Born in Essex to a Scottish mother, sent to George Heriot’s School, Edinburgh age 14.

In his final year at University he contracted TB before qualifying. His next three years were as a patient. He worked in Paris before moving to Southfield Sanatorium in Edinburgh, where he was a patient then to Edinburgh City Hospital. From 1939 to 1944, he was lecturer in the TB department at the University.

In 1944, he became physician superintendent at Lochmaben Sanatorium where he implemented high standards of food and hygiene, which proved effective.

Upon retirement 20 years later, TB was virtually eradicated at Lochmaben, with only five patients left.

In 1966 he became president of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. He chaired the Scottish Council for Postgraduate Education, responsible for coordinating the early career paths of general practitioners and hospital doctors.

Dr Clayson passed away at the age of 101 in Dumfries Infirmary.

In 1921, four pavilions were erected, these were originally hostels to house ammunition workers in Gretna. They were used for treating patients with tuberculosis, mainly of the lungs but also of bones, joints and glands. The old fever wards were closed in 1949 and the new hospital became known as Lochmaben Sanatorium serving the South-West of Scotland.

In 1946, Doctor Christopher Clayson was appointed Medical Superintendent of the Sanatorium. So acute was the demand for beds that in 1952, unless the sufferer was a young, active male spreading tubercle bacilli52, admission was through a waiting list.

It is a testament to the hospital and staff that, as a fever hospital, between 1908 and 1953 they had 5463 patient admissions of which 2817 had Scarlet Fever53, 1527 Diptheria54 and other admisions of 1119 which included conditions śuch as Typhoid55, Cerebro Spinal Fever (Meningitis)56 and Poliomyelitus57.

Sadly people die, however during this entire period Deaths totaled 218 – in other words, patients in this hospital had a survival rate of over 96%.

As new treatments came along the role of the hospital evolved. Beds in one pavilion were transferred to orthopaedic surgeons, and in another were given over to geriatrics

When Dr. Clayson retired in 1969, all beds for treatment of tuberculosis were phased out.

It is not possible to cover every member of staff who worked at the hospital but their dedication, kindness and compassion are noteworthy.

One example is a local resident Dr John Briddon Wilson, geriatrician.

In 1989 octogenarian Michael Spencer from Kirkmahoe was taken from DGRI to Lochmaben by Dr Wilson, when there was no more that could be done for him at Dumfries. His widow said “They were very kind to visitors at Lochmaben. … I happened to be visiting as lunchtime was approaching, and the sister presented me with a bowl of soup.“

She continued: “Michael was brought home for Christmas Day. … Two of the family had to take him back about 4 o’clock because we were concerned about him. Dr. J.B. Wilson turned out to talk to him on his return even though it was Christmas Day.“

Dr. Wilson said: “I don’t care even if it is Christmas Day, if I am wanted I’ll come.” “I was very impressed,” said Mrs. Spencer. “Michael died on New Year’s Eve.“

Lochmaben Hospital (2023)

The role of Lochmaben Hospital has evolved to meet changing societal needs and is currently (2023) a 14 bedded facility, consisting of 12 single rooms and 1 double room all with en-suite facilities58.

Provides short term care for people with a variety of physical and mental health problems requiring rehabilitation, or palliative care.

These beds are accessible by local GPs and consultants from Dumfries & Galloway Royal Infirmary.

As Gandhi said – “The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members“

How do we, as a caring society, stand up to that ideal?

Have we evolved enough to hold our heads high?

or

Is there more we should or could do to improve people’s lives?

Indeed

Do we care?

- https://www.rps.ac.uk/trans/1425/3/22[↩]

- https://scottishhistorysociety.com/the-scottish-reformation-c-1525-1560/[↩]

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zsdxsbk/revision/7[↩]

- https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/article/our-records-kirk-session-and-poor[↩]

- https://www.rps.ac.uk/trans/1579/10/27[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jougs[↩]

- https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/media/resources/9781474427289_Poor_Relief_and_the_Church_in_Scotland_Introduction.pdf[↩]

- https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/record-guides/kirk-session-records[↩]

- A heritor was a privileged person in a parish in Scots law. In its original acceptation, it signified the proprietor of a heritable subject, but, in the law relating to parish government, the term was confined to such proprietors of lands or houses as were liable, as written in their title deeds, for the payment of public burdens, such as the minister’s stipend, manse and glebe assessments, schoolmaster’s salary, poor rates, rogue-money (for preventing crime) as well as road and bridge assessments, and others like public and county burdens.[↩]

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/boundaries/history.html#histparish[↩]

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/i/industrial-revolution.asp#:~:text=The%20Industrial%20Revolution%20was%20a,exploitation%20of%20coal%20and%20iron.[↩]

- https://rcpsg.ac.uk/[↩]

- The History of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow: The Shaping of the Medical Profession, 1858-1999 Andrew Hull, Johanna Geyer-Kordesch: Hambledon Press, page 288[↩]

- Sinclair, Sir John. The Statistical Account of Scotland, Lochmaben, Dumfries, Vol. 7, Edinburgh: William Creech, 1793, p. 234 to 244. University of Edinburgh, University of Glasgow. (1999) The Statistical Accounts of Scotland online service: https://stataccscot.edina.ac.uk:443/link/osa-vol7-p244-parish-dumfries-lochmaben[↩]

- Parish of Lochmaben, Presbytery of Lochmaben, Synod of Dumfries: The Rev. Thomas Marjoribanks, Minister drawn up 1835, while the incumbency was vacant, by the Rev. John Gardiner, a native of Lochmaben. 1835[↩]

- James Richardson, merchant in Reading who died in 1726: Minutes of the Presbytery of Lochmaben 1701-1822: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/23103427/vol-51-dumfriesshire-galloway-natural-history-and-antiquarian-[↩]

- Legal Usage: to bequeath or allocate lands, property or money in perpetuity to a corporation or public body for specified religious, charitable or social purposes. https://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/mortify[↩]

- About £50,000 today (2023[↩]

- Statistical Account NUMBER XXII Parish of Lochmaben (County of Dumfries, District of Annandale.-Presbytery of Lochmaben.-Synod of Dumfries.) By the Reverend Mr Andrew Jaffray. 1793[↩]

- About £15,200 today (2023)[↩]

- In this context its meaning appears to be pointless[↩]

- About £1,900 today (2023)[↩]

- About £750 today (2023)[↩]

- About £48 today (2023[↩]

- A mortcloth (from the Latin mors meaning death) was a ceremonial cloth draped over a coffin (or a corpse if the family could not afford a coffin) at a funeral. Most families didn’t have their own mortcloths – not unreasonable when you consider that any one person only needs it once! – instead hiring them for the occasion. In burghs, the individual trades might have their own mortcloths which were lent to members for the occasion. But in most cases, mortcloths were available to hire from the Kirk Sessions. https://www.oldscottish.com/blog/m-is-for-mortcloth-money-and-morbidity[↩]

- https://www.oldscottish.com/lochmaben.html#Fathers[↩][↩]

- About £120 today (2023[↩]

- 1892 Extract of OS map courtesy of National Library of Scotland[↩]

- ((1892 Extract of OS map courtesy of National Library of Scotland[↩]

- The Royal Burgh of Lochmaben: Its History, Its Castles and Its Churches: by John B Wilson (1987[↩]

- Lochmaben Poorhouse built 1851 – Wardens Building? – Photo R Togneri[↩]

- Lochmaben Poorhouse built 1851 – End Building – Photo R Togneri[↩]

- https://www.workhouses.org.uk/Scotland/#:~:text=In%201579%2C%20an%20act%20of,for%20the%20next%20three%20centuries.[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Run_rig[↩]

- https://www.workhouses.org.uk/Scotland/rules1850.shtml[↩]

- ‘Fernought‘ or Fearnought’ was a stout woollen cloth, mainly used on ships as outside clothing tor bad weather. Linsey-Woolsey was a fabric Witn a linen, or sometimes cotton, warp and a wool wett — its name simply derived from “Lin” (an old name for flax) and “wool“.[↩]

- Grogram was a coarse fabric ot silk, or ot mohair and wool, or of a mixture of all these, often stiffened with gum.[↩]

- https://www.oldscottish.com/lochmaben.html#PoorAppeals[↩]

- https://www.oldscottish.com/lochmaben.html#PoorAppeals[↩]

- https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/1927-03-10/debates/95bf8457-14dc-445c-a8f5-97d2b0f49d62/PoorLawEmergencyProvisions(Scotland)Bill[↩]

- https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo5/19-20/25/contents[↩]

- https://www.socialsecurity.gov.scot/benefits[↩]

- https://www.politics.co.uk/reference/national-insurance/[↩]

- https://www.legislation.gov.uk/id/ukpga/1968/49[↩]

- History of Lochmaben Hospital: A Hospital Within Dumfries and Galloway Community Health N.H.S. Trust By Morag Williams · 1996[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_officer_of_health#:~:text=The%20post%20is%20held%20by,matters%20of%20public%20health%20importance.[↩]

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/i/industrial-revolution.asp#:~:text=The%20Industrial%20Revolution%20was%20a,exploitation%20of%20coal%20and%20iron.[↩]

- https://www.scottisharchitects.org.uk/architect_full.php?id=200341[↩]

- Lochmaben Sanatorium Location – extract from 1949 OS map courtesy of National Library of Scotland[↩]

- Aerofilms photograph of Lochmaben Hospital taken in 1929, from the RCAHMS collection[↩]

- https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw59917/Ethel-Mary-ne-Piercy-Lady-Buchanan-Jardine[↩]

- a bacterium that causes tuberculosi[↩]

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/scarlet-fever/[↩]

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/diphtheria/[↩]

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/typhoid-fever/[↩]

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/meningitis/[↩]

- https://www.who.int/health-topics/poliomyelitis#tab=tab_1[↩]

- https://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/our_work/inspecting_and_regulating_care/nhs_hospitals_and_services/nhs_dumfries__galloway/lochmaben_hospital.aspx[↩]